Foundations of Freedom of Expression

OpenStax and Lumen Learning; Tom Rozinski; and Collected works

5.1 Introduction to The Media

Democratic primary candidate Bernie Sanders arrived in Seattle on August 8, 2015, to give a speech at a rally to promote his presidential campaign. Instead, the rally was interrupted—and eventually co-opted—by activists for Black Lives Matter (Figure 5.1).[1] Why did the group risk alienating Democratic voters by preventing Sanders from speaking? Because Black Lives Matter had been trying to raise awareness of the treatment of Black citizens in the United States, and the media has the power to elevate such issues.[2] While some questioned its tactics, the organization’s move underscores how important the media are to gaining recognition, and the lengths to which organizations are willing to go to get media attention.[3]

Freedom of the press and an independent media are important dimensions of a liberal society and a necessary part of a healthy democracy. “No government ought to be without censors,” said Thomas Jefferson, “and where the press is free, no one ever will.”[4] What does it mean to have a free news media? What regulations limit what media can do? How do the media contribute to informing citizens and monitoring politicians and the government, and how do we measure their impact? This chapter explores these and other questions about the role of the media in the United States.

5.2 What Is the Media?

LEARNING OUTCOMES

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain what the media are and how they are organized

- Describe the main functions of the media in a free society

- Compare different media formats and their respective audiences

Ours is an exploding media system. What started as print journalism was subsequently supplemented by radio coverage, then network television, followed by cable television. Now, with the addition of the Internet, blogs and social media—a set of applications or web platforms that allow users to immediately communicate with one another—give citizens a wide variety of sources for instant news of all kinds. The Internet also allows citizens to initiate public discussion by uploading images and video for viewing, such as videos documenting interactions between citizens and the police, for example. Provided we are connected digitally, we have a bewildering amount of choices for finding information about the world. In fact, some might say that compared to the tranquil days of the 1970s, when we might read the morning newspaper over breakfast and take in the network news at night, there are now too many choices in today’s increasingly complex world of information. This reality may make the news media all the more important to structuring and shaping narratives about U.S. politics. Or the proliferation of competing information sources like blogs and social media may actually weaken the power of the news media relative to the days when news media monopolized our attention.

Media Basics

The term media defines a number of different communication formats from television media, which share information through broadcast airwaves, to print media, which rely on printed documents. The collection of all forms of media that communicate information to the general public is called mass media, including television, print, radio, and Internet. One of the primary reasons citizens turn to the media is for news. We expect the media to cover important political and social events and information in a concise and neutral manner.

To accomplish its work, the media employs a number of people in varied positions. Journalists and reporters are responsible for uncovering news stories by keeping an eye on areas of public interest, like politics, business, and sports. Once a journalist has a lead or a possible idea for a story, they research background information and interview people to create a complete and balanced account. Editors work in the background of the newsroom, assigning stories, approving articles or packages, and editing content for accuracy and clarity. Publishers are people or companies that own and produce print or digital media. They oversee both the content and finances of the publication, ensuring the organization turns a profit and creates a high-quality product to distribute to consumers. Producers oversee the production and finances of visual media, like television, radio, and film.

The work of the news media differs from public relations, which is communication carried out to improve the image of companies, organizations, or candidates for office. Public relations is not a neutral information form. While journalists write stories to inform the public, a public relations spokesperson is paid to help an individual or organization get positive press. Public relations materials normally appear as press releases or paid advertisements in newspapers and other media outlets. Some less reputable publications, however, publish paid articles under the news banner, blurring the line between journalism and public relations.

Media Types

LINK TO LEARNING

*Watch this video to learn more about the power and influence of media in politics.

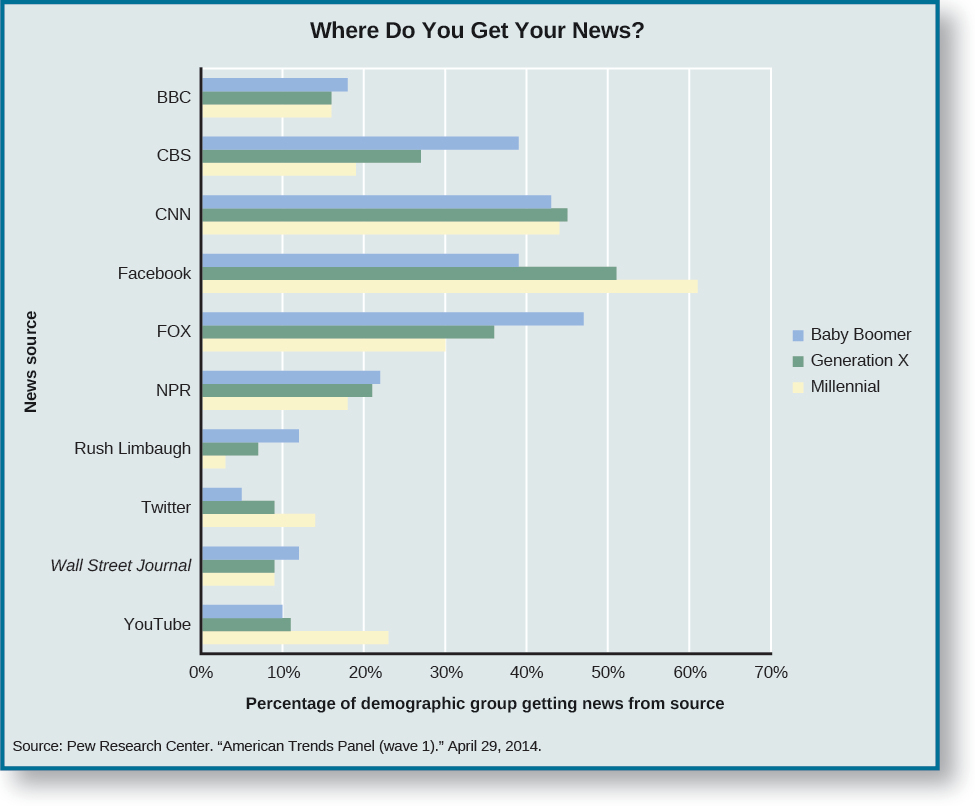

Each form of media has its own complexities and is used by different demographics. Millennials (those born between 1981 and 1996) and Generation Z (those born between 1997 and 2012) are more likely to get news and information from social media, such as Instagram, TikTok, Twitter, and YouTube, while Baby Boomers (born between 1946 and 1964) are most likely to get their news from television, either national broadcasts or local news (Figure 5.2).

Television alone offers viewers a variety of formats. Programming may be scripted, like dramas or comedies. It may be unscripted, like game shows or reality programs, or informative, such as news programming. Although most programs are created by a television production company, national networks—like CBS or NBC—purchase the rights to programs they distribute to local stations across the United States. Most local stations are affiliated with a national network corporation, and they broadcast national network programming to their local viewers.

Before the existence of cable and fiber optics, networks needed to own local affiliates to have access to the local station’s transmission towers. Towers have a limited radius, so each network needed an affiliate in each major city to reach viewers. While cable technology has lessened networks’ dependence on aerial signals, some viewers still use antennas and receivers to view programming broadcast from local towers.

Affiliates, by agreement with the networks, give priority to network news and other programming chosen by the affiliate’s national media corporation. Local affiliate stations are told when to air programs or commercials, and they diverge only to inform the public about a local or national emergency. For example, ABC affiliates broadcast the popular television show Black-ish at a specific time on a specific day. Should a fire threaten homes and businesses in a local area, the affiliate might preempt it to update citizens on the fire’s dangers and return to regularly scheduled programming after the danger has ended.

Most affiliate stations will show local news before and after network programming to inform local viewers of events and issues. Network news has a national focus on politics, international events, the economy, and more. Local news, on the other hand, is likely to focus on matters close to home, such as regional business, crime, sports, and weather.[5] The NBC Nightly News, for example, covers presidential campaigns and the White House or skirmishes between North Korea and South Korea, while the NBC affiliate in Los Angeles (KNBC-TV) and the NBC affiliate in Dallas (KXAS-TV) report on the governor’s activities or weekend festivals in the region.

Cable programming offers national networks a second method to directly reach local viewers. As the name implies, cable stations transmit programming directly to a local cable company hub, which then sends the signals to homes through coaxial or fiber optic cables. Because cable does not broadcast programming through the airwaves, cable networks can operate across the nation directly without local affiliates. Instead, they purchase broadcasting rights for the cable stations they believe their viewers want. For this reason, cable networks often specialize in different types of programming.

The Cable News Network (CNN) was the first news station to take advantage of this specialized format, creating a 24-hour news station with live coverage and interview programs. Other news stations quickly followed, such as MSNBC and FOX News. A viewer might tune in to Nickelodeon and catch family programs and movies or watch ESPN to catch up with the latest baseball or basketball scores. The Cable-Satellite Public Affairs Network, known better as C-SPAN, now has three channels covering Congress, the president, the courts, and matters of public interest.

Cable and satellite providers also offer on-demand programming for most stations. Citizens can purchase cable, satellite, and Internet subscription services (like Netflix) to find programs to watch instantly, without being tied to a schedule. Initially, on-demand programming was limited to rebroadcasting old content and was commercial-free. Yet many networks and programs now allow their new programming to be aired within a day or two of its initial broadcast. In return they often add commercials the user cannot fast-forward or avoid. Thus networks expect advertising revenues to increase.[6]

The on-demand nature of the Internet has created many opportunities for news outlets. While early media providers were those who could pay the high cost of printing or broadcasting, modern media require just a URL and ample server space. The ease of online publication has made it possible for more niche media outlets to form. The websites of the New York Times and other newspapers often focus on matters affecting the United States, while channels like BBC America present world news. FOX News presents political commentary and news in a conservative vein, while the Internet site Daily Kos offers a liberal perspective on the news. Politico.com is perhaps the leader in niche journalism.

Unfortunately, the proliferation of online news has also increased the amount of poorly written material with little editorial oversight, and readers must be cautious when reading Internet news sources. Sites like Buzzfeed allow members to post articles without review by an editorial board, leading to articles of varied quality and accuracy. The Internet has also made publication speed a consideration for professional journalists. No news outlet wants to be the last to break a story, and the rush to publication often leads to typographical and factual errors. Even large news outlets, like the Associated Press, have published articles with errors in their haste to get a story out.

The Internet also facilitates the flow of information through social media, which allows users to instantly communicate with one another and share with audiences that can grow exponentially. Facebook and Twitter have millions of daily users. Social media changes more rapidly than the other media formats. While people in many different age groups use sites like Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube, other sites like Snapchat and TikTok appeal mostly to younger users. The platforms also serve different functions. Tumblr and Reddit facilitate discussion that is topic-based and controversial, while Instagram is mostly social. A growing number of these sites also allow users to comment anonymously, leading to increases in threats and abuse. The 2020 QAnon conspiracy, which absurdly alleged a connection between liberal elites and child sex trafficking, was promulgated in part through social media posts on many platforms, including Facebook and Twitter. Both companies attempted to kick QAnon off their platforms.[7]

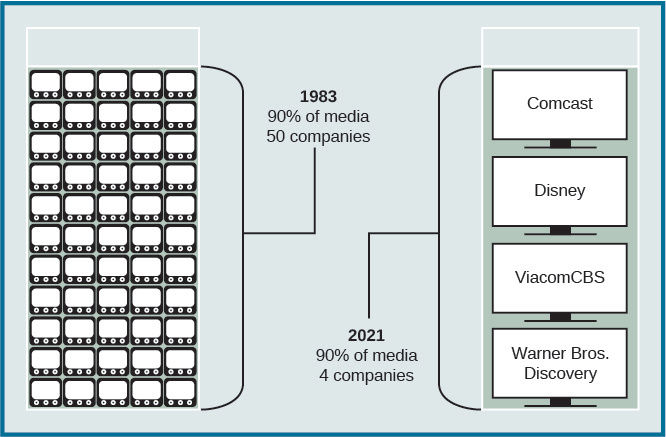

Regardless of where we get our information, the various media avenues available today, versus years ago, make it much easier for everyone to be engaged. The question is: Who controls the media we rely on? Most media are controlled by a limited number of conglomerates. A conglomerate is a corporation made up of a number of companies, organizations, and media networks. In the 1980s, more than fifty companies owned the majority of television and radio stations and networks. By 2011, six conglomerates controlled most of the broadcast media in the United States: CBS Corporation, Comcast, Time Warner, 21st Century Fox (formerly News Corporation), Viacom, and The Walt Disney Company (Figure 5.3).[8]

Newspapers too have experienced the pattern of concentrated ownership. Gannett Company, while also owning television media, holds a large number of newspapers and news magazines in its control. Many of these were acquired quietly, without public notice or discussion. Gannett’s 2013 acquisition of publishing giant A.H. Belo Corporation caused some concern and news coverage, however. The sale would have allowed Gannett to own both an NBC and a CBS affiliate in St. Louis, Missouri, giving it control over programming and advertising rates for two competing stations. The U.S. Department of Justice required Gannett to sell the station owned by Belo to ensure market competition and multi-ownership in St. Louis.[9]

LINK TO LEARNING

If you are concerned about the lack of variety in the media and the market dominance of media conglomerates, the non-profit organization, Free Press, tracks and promotes open communication.

These changes in the format and ownership of media raise the question whether the media still operate as an independent source of information. Is it possible that corporations and CEOs now control the information flow, making profit more important than the impartial delivery of information? The reality is that media outlets, whether newspaper, television, radio, or Internet, are businesses. They have expenses and must raise revenues. Yet at the same time, we expect the media to entertain, inform, and alert us without bias. They must provide some public services, while following laws and regulations. Reconciling these goals may not always be possible.

Functions of the Media

The media exist to fill a number of functions. Whether the medium is a newspaper, a radio, or a television newscast, a corporation behind the scenes must bring in revenue and pay for the cost of the product. Revenue comes from advertising and sponsors, like McDonald’s, Ford Motor Company, and other large corporations. But corporations will not pay for advertising if there are no viewers or readers. So all programs and publications need to entertain, inform, or interest the public and maintain a steady stream of consumers. In the end, what attracts viewers and advertisers is what survives.

The media are also watchdogs of society and of public officials. Some refer to the media as the fourth estate, with the branches of government being the first three estates and the media equally participating as the fourth. This role helps maintain democracy and keeps the government accountable for its actions, even if a branch of the government is reluctant to open itself to public scrutiny. As much as social scientists would like citizens to be informed and involved in politics and events, the reality is that we are not. So the media, especially journalists, keep an eye on what is happening and sounds an alarm when the public needs to pay attention.[10]

The media also engages in agenda setting, which is the act of choosing which issues or topics deserve public discussion. For example, in the early 1980s, famine in Ethiopia drew worldwide attention, which resulted in increased charitable giving to the country. Yet the famine had been going on for a long time before it was discovered by western media. Even after the discovery, it took video footage to gain the attention of the British and U.S. populations and start the aid flowing.[11] Today, numerous examples of agenda setting show how important the media are when trying to prevent further emergencies or humanitarian crises. In the spring of 2015, when the Dominican Republic was preparing to exile Haitians and undocumented (or under documented) residents, major U.S. news outlets remained silent. However, once the story had been covered several times by Al Jazeera, a state-funded broadcast company based in Qatar, ABC, the New York Times, and other network outlets followed.[12] With major network coverage came public pressure for the U.S. government to act on behalf of the Haitians.[13]

INSIDER PERSPECTIVE

Christiane Amanpour on “What Should Be News?”

The media are our connection to the world. Some events are too big to ignore, yet other events, such as the destruction of Middle Eastern monuments or the plight of foreign refugees, are far enough from our shores that they often go unnoticed. What we see is carefully selected, but who decides what should be news?

As the chief international correspondent for CNN, Christiane Amanpour is one media decision maker (Figure 5.4). Over the years, Amanpour has covered events around the world from war to genocide. In an interview with Oprah Winfrey, Amanpour explains that her duty, and that of other journalists, is to make a difference in the world. To do that, “we have to educate people and use the media responsibly.”[14] Journalists cannot passively sit by and wait for stories to find them. “Words have consequences: the stories we decide to do, the stories we decide not to do . . . it all matters.”[15]

As Amanpour points out, journalists are often “on the cutting edge of reform,” so if they fail to shed light on events, the results can be tragic. One of her biggest regrets was not covering the genocide in Rwanda in 1994, which cost nearly a million lives. She said the media ignored the event in favor of covering democratic elections in South Africa and a war in Bosnia, and ultimately she believes the media failed the people. “If we don’t respect our profession and we see it frittering away into the realm of triviality and sensationalism, we’ll lose our standing,” she said. “That won’t be good for democracy. A thriving society must have a thriving press.”

This feeling of responsibility extends to covering moral topics, like genocide. Amanpour feels there shouldn’t be equal time given to all sides. “I’m not just a stenographer or someone with a megaphone; when I report, I have to do it in context, to be aware of the moral conundrum. . . . I have to be able to draw a line between victim and aggressor.”

Amanpour also believes the media should cover more. When given the full background and details of events, society pays attention to the news. “Individual Americans had an incredible reaction to the [2004 Indian Ocean] tsunami—much faster than their government’s reaction,” she said. “Americans are a very moral and compassionate people who believe in extending a helping hand, especially when they get the full facts instead of one-minute clips.” If the news fulfills its responsibility, as she sees it, the world can show its compassion and help promote freedom.

Why does Amanpour believe the press has a responsibility to report all that they see? Are there situations in which it is acceptable to display partiality in reporting the news? Why or why not?

Before the Internet, traditional media determined whether citizen photographs or video footage would become “news.” In 1991, a private citizen’s camcorder footage showed four police officers beating an African American motorist named Rodney King in Los Angeles. After appearing on local independent television station, KTLA-TV, and then the national news, the event began a national discussion on police brutality and ignited riots in Los Angeles.[16] The agenda-setting power of traditional media has begun to be appropriated by social media and smartphones, however. Twitter, Facebook, YouTube, and other Internet sites allow witnesses to instantly upload images and accounts of events and forward the link to friends. Some uploads go viral and attract the attention of the mainstream media, but large network newscasts and major newspapers are still more powerful at initiating or changing a discussion.

The media also promote the public good by offering a platform for public debate and improving citizen awareness. Network news informs the electorate about national issues, elections, and international news. The New York Times, Los Angeles Times, NBC Nightly News, and other outlets make sure voters can easily find out what issues affect the nation. Is terrorism on the rise? Is the dollar weakening? The network news hosts national debates during presidential elections, broadcasts major presidential addresses, and interviews political leaders during times of crisis. Cable news networks now provide coverage of all these topics as well.

Local news has a larger job, despite small budgets and fewer resources (Figure 5.5). Local government and local economic policy have a strong and immediate effect on citizens. Is the city government planning on changing property tax rates? Will the school district change the way Common Core tests are administered? When and where is the next town hall meeting or public forum to be held? Local and social media provide a forum for protest and discussion of issues that matter to the community.

LINK TO LEARNING

Want a snapshot of local and state political and policy news? The magazine Governing keeps an eye on what is happening in each state, offering articles and analysis on events that occur across the country.

While journalists reporting the news try to present information in an unbiased fashion, sometimes the public seeks opinion and analysis of complicated issues that affect various populations differently, like healthcare reform and the Affordable Care Act. This type of coverage may come in the form of editorials, commentaries, Op-Ed columns, and blogs. These forums allow the editorial staff and informed columnists to express a personal belief and attempt to persuade. If opinion writers are trusted by the public, they have influence.

Walter Cronkite, reporting from Vietnam, had a loyal following. In a broadcast following the Tet Offensive in 1968, Cronkite expressed concern that the United States was mired in a conflict that would end in a stalemate.[17] His coverage was based on opinion after viewing the war from the ground.[18] Although the number of people supporting the war had dwindled by this time, Cronkite’s commentary bolstered opposition. Like editorials, commentaries contain opinion and are often written by specialists in a field. Larry Sabato, a prominent political science professor at the University of Virginia, occasionally writes his thoughts for the New York Times. These pieces are based on his expertise in politics and elections.[19] Blogs offer more personalized coverage, addressing specific concerns and perspectives for a limited group of readers. As of 2021, the most popular blog on U.S. politics was The Daily Kos, a liberal blog with 25 million followers each month.[20]

5.3 The Evolution of the Media

LEARNING OUTCOMES

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Discuss the history of major media formats

- Compare important changes in media types over time

- Explain how citizens learn political information from the media

The evolution of the media has been fraught with concerns and problems. Accusations of mind control, bias, and poor quality have been thrown at the media on a regular basis. Yet the growth of communications technology allows people today to find more information more easily than any previous generation. Mass media can be print, radio, television, or Internet news. They can be local, national, or international. They can be broad or limited in their focus. The choices are tremendous.

Print Media

Early news was presented to local populations through the print press. While several colonies had printers and occasional newspapers, high literacy rates combined with the desire for self-government made Boston a perfect location for the creation of a newspaper, and the first continuous press was started there in 1704.[21] Newspapers spread information about local events and activities. The Stamp Tax of 1765 raised costs for publishers, however, leading several newspapers to fold under the increased cost of paper. The repeal of the Stamp Tax in 1766 quieted concerns for a short while, but editors and writers soon began questioning the right of the British to rule over the colonies. Newspapers took part in the effort to inform citizens of British misdeeds and incite attempts to revolt. Readership across the colonies increased to nearly forty thousand homes (among a total population of two million), and daily papers sprang up in large cities.[22]

Although newspapers united for a common cause during the Revolutionary War, the divisions that occurred during the Constitutional Convention and the United States’ early history created a change. The publication of the Federalist Papers, as well as the Anti-Federalist Papers, in the 1780s, moved the nation into the party press era, in which partisanship and political party loyalty dominated the choice of editorial content. One reason was cost. Subscriptions and advertisements did not fully cover printing costs, and political parties stepped in to support presses that aided the parties and their policies. Papers began printing party propaganda and messages, even publicly attacking political leaders like George Washington. Despite the antagonism of the press, Washington and several other founders felt that freedom of the press was important for creating an informed electorate. Indeed, freedom of the press is enshrined in the Bill of Rights in the first amendment.

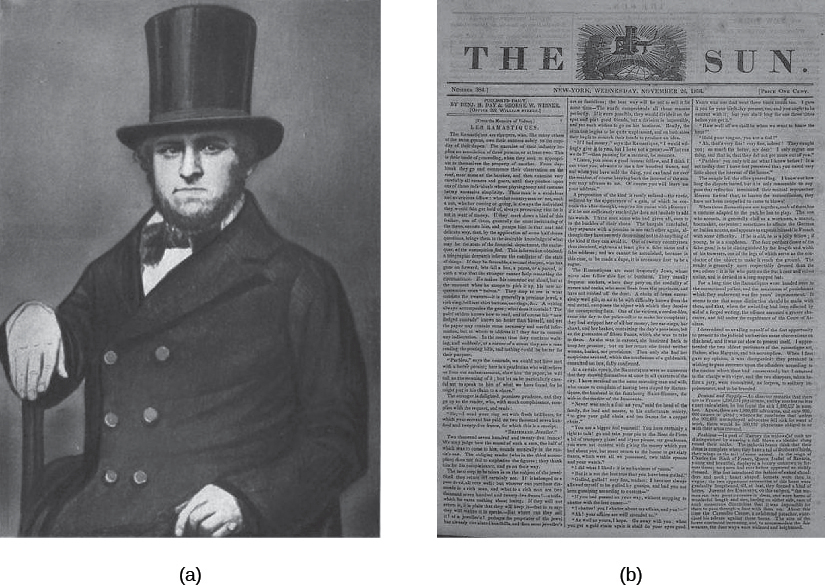

Between 1830 and 1860, machines and manufacturing made the production of newspapers faster and less expensive. Benjamin Day’s paper, the New York Sun, used technology like the linotype machine to mass-produce papers (Figure 5.6). Roads and waterways were expanded, decreasing the costs of distributing printed materials to subscribers. New newspapers popped up. The popular penny press papers and magazines contained more gossip than news, but they were affordable at a penny per issue. Over time, papers expanded their coverage to include racing, weather, and educational materials. By 1841, some news reporters considered themselves responsible for upholding high journalistic standards, and under the editor (and politician) Horace Greeley, the New-York Tribune became a nationally respected newspaper. By the end of the Civil War, more journalists and newspapers were aiming to meet professional standards of accuracy and impartiality.[23]

Yet readers still wanted to be entertained. Joseph Pulitzer and the New York World gave them what they wanted. The tabloid-style paper included editorial pages, cartoons, and pictures, while the front-page news was sensational and scandalous. This style of coverage became known as yellow journalism. Ads sold quickly thanks to the paper’s popularity, and the Sunday edition became a regular feature of the newspaper. As the New York World’s circulation increased, other papers copied Pulitzer’s style in an effort to sell papers. Competition between newspapers led to increasingly sensationalized covers and crude issues.

In 1896, Adolph Ochs purchased the New York Times with the goal of creating a dignified newspaper that would provide readers with important news about the economy, politics, and the world rather than gossip and comics. The New York Times brought back the informational model, which exhibits impartiality and accuracy and promotes transparency in government and politics. With the arrival of the Progressive Era, the media began muckraking: the writing and publishing of news coverage that exposed corrupt business and government practices. Investigative work like Upton Sinclair’s serialized novel The Jungle led to changes in the way industrial workers were treated and local political machines were run. The Pure Food and Drug Act and other laws were passed to protect consumers and employees from unsafe food processing practices. Local and state government officials who participated in bribery and corruption became the centerpieces of exposés.

Some muckraking journalism still appears today, and the quicker movement of information through the system would seem to suggest an environment for yet more investigative work and the punch of exposés than in the past. However, at the same time there are fewer journalists being hired than there used to be. The scarcity of journalists and the lack of time to dig for details in a 24-hour, profit-oriented news model make investigative stories rare.[24] There are two potential concerns about the decline of investigative journalism in the digital age. First, one potential shortcoming is that the quality of news content will become uneven in depth and quality, which could lead to a less informed citizenry. Second, if investigative journalism in its systematic form declines, then the cases of wrongdoing that are the objects of such investigations would have a greater chance of going on undetected.

In the twenty-first century, newspapers have struggled to stay financially stable. Print media earned $46 billion from ads in 2012, but only $20.5 billion from ads in 2020.[25] Given the countless alternate forms of news, many of which are free, newspaper subscriptions have fallen. Advertising and especially classified ad revenue dipped. Many newspapers now maintain both a print and an Internet presence in order to compete for readers. The rise of free news blogs, such as the Huffington Post, have made it difficult for newspapers to force readers to purchase online subscriptions to access material they place behind a digital paywall. Some local newspapers, in an effort to stay visible and profitable, have turned to social media, like Facebook and Twitter. Stories can be posted and retweeted, allowing readers to comment and forward material.[26] Yet, overall, newspapers have adapted, becoming leaner—though less thorough and investigative—versions of their earlier selves. However, despite this adaptation, one-fifth of small-town newspapers have folded. The fear is that Americans will know less about their community as a result.[27] This drop-off in available news has also occurred at the state level, as state legislative press corps have shrunk considerably. Many surviving small-town papers have been acquired by larger conglomerates. National newspapers have done comparatively better, although consolidation has occurred there to some degree, too.[28]

Radio

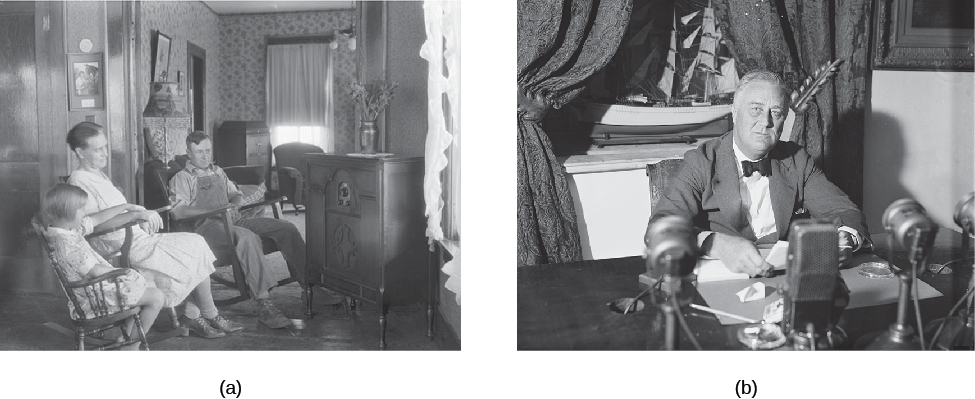

Radio news made its appearance in the 1920s. The National Broadcasting Company (NBC) and the Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS) began running sponsored news programs and radio dramas. Comedy programs, such as Amos ’n’ Andy, The Adventures of Gracie, and Easy Aces, also became popular during the 1930s, as listeners were trying to find humor during the Depression (Figure 5.7). Talk shows, religious shows, and educational programs followed, and by the late 1930s, game shows and quiz shows were added to the airwaves. Almost 83 percent of households had a radio by 1940, and most tuned in regularly.[29]

Not just something to be enjoyed by those in the city, the proliferation of the radio brought communications to rural America as well. News and entertainment programs were also targeted to rural communities. WLS in Chicago provided the National Farm and Home Hour and the WLS Barn Dance. WSM in Nashville began to broadcast the live music show called the Grand Ole Opry, which is still broadcast every week and is the longest live broadcast radio show in U.S. history.[30]

As radio listenership grew, politicians realized that the medium offered a way to reach the public in a personal manner. Warren Harding was the first president to regularly give speeches over the radio. President Herbert Hoover used radio as well, mainly to announce government programs on aid and unemployment relief.[31] Yet it was Franklin D. Roosevelt who became famous for harnessing the political power of radio. On entering office in March 1933, President Roosevelt needed to quiet public fears about the economy and prevent people from removing their money from the banks. He delivered his first radio speech eight days after assuming the presidency:

“My friends: I want to talk for a few minutes with the people of the United States about banking—to talk with the comparatively few who understand the mechanics of banking, but more particularly with the overwhelming majority of you who use banks for the making of deposits and the drawing of checks. I want to tell you what has been done in the last few days, and why it was done, and what the next steps are going to be.”[32]

Roosevelt spoke directly to the people and addressed them as equals. One listener described the chats as soothing, with the president acting like a father, sitting in the room with the family, cutting through the political nonsense and describing what help he needed from each family member.[33]Roosevelt would sit down and explain his ideas and actions directly to the people on a regular basis, confident that he could convince voters of their value.[34] His speeches became known as “fireside chats” and formed an important way for him to promote his New Deal agenda (Figure 5.8). Roosevelt’s combination of persuasive rhetoric and the media allowed him to expand both the government and the presidency beyond their traditional roles.[35]

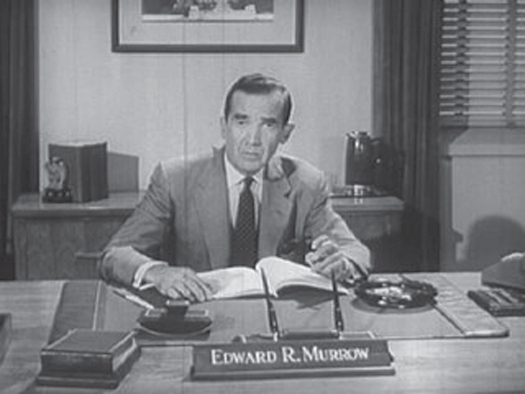

During this time, print news still controlled much of the information flowing to the public. Radio news programs were limited in scope and number. But in the 1940s the German annexation of Austria, conflict in Europe, and World War II changed radio news forever. The need and desire for frequent news updates about the constantly evolving war made newspapers, with their once-a-day printing, too slow. People wanted to know what was happening, and they wanted to know immediately. Although initially reluctant to be on the air, reporter Edward R. Murrow of CBS began reporting live about Germany’s actions from his posts in Europe. His reporting contained news and some commentary, and even live coverage during Germany’s aerial bombing of London. To protect covert military operations during the war, the White House had placed guidelines on the reporting of classified information, making a legal exception to the First Amendment’s protection against government involvement in the press. Newscasters voluntarily agreed to suppress information, such as about the development of the atomic bomb and movements of the military, until after the events had occurred.[36]

The number of professional and amateur radio stations grew quickly. Initially, the government exerted little legislative control over the industry. Stations chose their own broadcasting locations, signal strengths, and frequencies, which sometimes overlapped with one another or with the military, leading to tuning problems for listeners. The Radio Act (1927) created the Federal Radio Commission (FRC), which made the first effort to set standards, frequencies, and license stations. The Commission was under heavy pressure from Congress, however, and had little authority. The Communications Act of 1934 ended the FRC and created the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), which continued to work with radio stations to assign frequencies and set national standards, as well as oversee other forms of broadcasting and telephones. The FCC regulates interstate communications to this day. For example, it prohibits the use of certain profane words during certain hours on public airwaves.

Prior to WWII, radio frequencies were broadcast using amplitude modulation (AM). After WWII, frequency modulation (FM) broadcasting, with its wider signal bandwidth, provided clear sound with less static and became popular with stations wanting to broadcast speeches or music with high-quality sound. While radio’s importance for distributing news waned with the increase in television usage, it remained popular for listening to music, educational talk shows, and sports broadcasting. Talk stations began to gain ground in the 1980s on both AM and FM frequencies, restoring radio’s importance in politics. By the 1990s, talk shows had gone national, showcasing broadcasters like Rush Limbaugh and Don Imus.

In 1990, Sirius Satellite Radio began a campaign for FCC approval of satellite radio. The idea was to broadcast digital programming from satellites in orbit, eliminating the need for local towers. By 2001, two satellite stations had been approved for broadcasting. Satellite radio has greatly increased programming with many specialized offerings, such as channels dedicated to particular artists. It is generally subscription-based and offers a larger area of coverage, even to remote areas such as deserts and oceans. Satellite programming is also exempt from many of the FCC regulations that govern regular radio stations. Howard Stern, for example, was fined more than $2 million while on public airwaves, mainly for his sexually explicit discussions.[37] Stern moved to Sirius Satellite in 2006 and has since been free of oversight and fines.

In a related vein, which speaks to the blurring of radio with the internet, is the explosion in podcasting. These audio shows, which are usually original but can be recorded versions of existing radio programs, explore a variety of topics and are enjoyed by millions of people around the world. They are especially popular for those who commute to and from work, but can be enjoyed anywhere, anytime. Total U.S. podcast listeners are a whopping 106.7 million, with 77.9 million listening to a podcast at least once per week. According to Business Insider: "A proliferation of shows, involvement from celebrity talent, investment from large companies like Spotify, and the spread of technologies that boost awareness, like smart speakers, have all helped podcast growth."[38] Podcasts with celebrity hosts include those offered by Anna Faris, Ricky Gervais and Stephen Merchant, and John Oliver.[39]

Television

Television combined the best attributes of radio and pictures and changed media forever. The first official broadcast in the United States was President Franklin Roosevelt’s speech at the opening of the 1939 World’s Fair in New York. The public did not immediately begin buying televisions, but coverage of World War II changed their minds. CBS reported on war events and included pictures and maps that enhanced the news for viewers. By the 1950s, the price of television sets had dropped, more televisions stations were being created, and advertisers were buying up spots.

As on the radio, quiz shows and games dominated the television airwaves. But when Edward R. Murrow made the move to television in 1951 with his news show See It Now, television journalism gained its foothold (Figure 5.9). As television programming expanded, more channels were added. Networks such as ABC, CBS, and NBC began nightly newscasts, and local stations and affiliates followed suit.

Even more than radio, television allows politicians to reach out and connect with citizens and voters in deeper ways. Before television, few voters were able to see a president or candidate speak or answer questions in an interview. Now everyone can decode body language and tone to decide whether candidates or politicians are sincere. Presidents can directly convey their anger, sorrow, or optimism during addresses.

The first television advertisements, run by presidential candidates Dwight D. Eisenhower and Adlai Stevenson in the early 1950s, were mainly radio jingles with animation or short question-and-answer sessions. In 1960, John F. Kennedy’s campaign used a Hollywood-style approach to promote his image as young and vibrant. The Kennedy campaign ran interesting and engaging ads, featuring Kennedy, his wife Jacqueline, and everyday citizens who supported him.

Television was also useful to combat scandals and accusations of impropriety. Republican vice presidential candidate Richard Nixon used a televised speech in 1952 to address accusations that he had taken money from a political campaign fund illegally. Nixon laid out his finances, investments, and debts and ended by saying that the only election gift the family had received was a cocker spaniel the children named Checkers.[40] The “Checkers speech” was remembered more for humanizing Nixon than for proving he had not taken money from the campaign account. Yet it was enough to quiet accusations. Democratic vice presidential nominee Geraldine Ferraro similarly used television to answer accusations in 1984, holding a televised press conference to answer questions for over two hours about her husband’s business dealings and tax returns.[41]

In addition to television ads, the 1960 election also featured the first televised presidential debate. By that time most households had a television. Kennedy’s careful grooming and practiced body language allowed viewers to focus on his presidential demeanor. His opponent, Richard Nixon, was still recovering from a severe case of the flu. While Nixon’s substantive answers and debate skills made a favorable impression on radio listeners, viewers’ reaction to his sweaty appearance and obvious discomfort demonstrated that live television had the potential to make or break a candidate.[42] In 1964, Lyndon B. Johnson was ahead in the polls, and he let Barry Goldwater’s campaign know he did not want to debate.[43] Nixon, who ran for president again in 1968 and 1972, declined to debate. Then in 1976, President Gerald Ford, who was behind in the polls, invited Jimmy Carter to debate, and televised debates became a regular part of future presidential campaigns.[44]

LINK TO LEARNING

Between the 1960s and the 1990s, presidents often used television to reach citizens and gain support for policies. When they made speeches, the networks and their local affiliates carried them. With few independent local stations available, a viewer had little alternative but to watch. During this “Golden Age of Presidential Television,” presidents had a strong command of the media.[45]

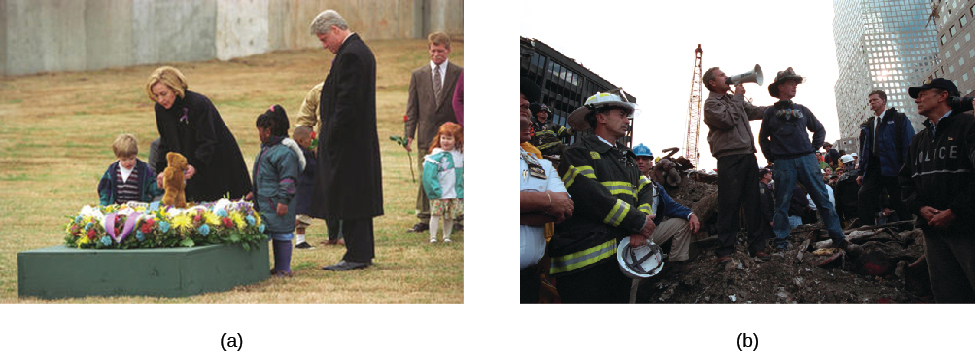

Some of the best examples of this power occurred when presidents used television to inspire and comfort the population during a national emergency. These speeches aided in the “rally ’round the flag” phenomenon, which occurs when a population feels threatened and unites around the president.[46] During these periods, presidents may receive heightened approval ratings, in part due to the media’s decision about what to cover.[47] In 1995, President Bill Clinton comforted and encouraged the families of the employees and children killed at the bombing of the Oklahoma City Federal Building. Clinton reminded the nation that children learn through action, and so we must speak up against violence and face evil acts with good acts.[48]

Following the terrorist attacks in New York and Washington on September 11, 2001, President George W. Bush’s bullhorn speech from the rubble of Ground Zero in New York similarly became a rally. Bush spoke to the workers and first responders and encouraged them, but his short speech became a viral clip demonstrating the resilience of New Yorkers and the anger of a nation.[49] He told New Yorkers, the country, and the world that Americans could hear the frustration and anguish of New York, and that the terrorists would soon hear the United States (Figure 5.10).

Following their speeches, both presidents also received a bump in popularity. Clinton’s approval rating rose from 46 to 51 percent, and Bush’s from 51 to 90 percent.[50]

New Media Trends

The invention of cable in the 1980s and the expansion of the Internet in the 2000s opened up more options for media consumers than ever before. Viewers can watch nearly anything at the click of a button, bypass commercials, and record programs of interest. The resulting saturation, or inundation of information, may lead viewers to abandon the news entirely or become more suspicious and fatigued about politics.[51] This effect, in turn, also changes the president’s ability to reach out to citizens. For example, viewership of the president’s annual State of the Union address has decreased over the years, from sixty-seven million viewers in 1993 to thirty-two million in 2015.[52] Citizens who want to watch reality television and movies can easily avoid the news, leaving presidents with no sure way to communicate with the public.[53] Other voices, such as those of talk show hosts and political pundits, now fill the gap.

Electoral candidates have also lost some media ground. In horse-race coverage, modern journalists analyze campaigns and blunders or the overall race, rather than interviewing the candidates or discussing their issue positions. Some argue that this shallow coverage is a result of candidates’ trying to control the journalists by limiting interviews and quotes. In an effort to regain control of the story, journalists begin analyzing campaigns without input from the candidates.[54] The use of social media by candidates provides a countervailing trend. President Trump’s hundreds of election tweets in 2016 are the stuff of legend. He continued to tweet with gusto as president and during the 2020 election, at times surprising even those who worked for him with the subject areas being tweeted about. The presidential tweet replaced the presidential press conference. Ultimately, in the wake of the January 6th insurrection at the U.S. Capitol, Twitter closed down Trump's account after he repeatedly raised topics and points that were of questionable veracity. Facebook and Instagram also followed suit with their own bans.[55]

MILESTONE

The First Social Media Candidate

When president-elect Barack Obama admitted an addiction to his Blackberry, the signs were clear: A new generation was assuming the presidency.[56] Obama’s use of technology was a part of life, not a campaign pretense. Perhaps for this reason, he was the first candidate to fully embrace social media.

While John McCain, the 2008 Republican presidential candidate, focused on traditional media to run his campaign, Obama did not. One of Obama’s campaign advisors was Chris Hughes, a cofounder of Facebook. The campaign allowed Hughes to create a powerful online presence for Obama, with sites on YouTube, Facebook, MySpace, and more. Podcasts and videos were available for anyone looking for information about the candidate. These efforts made it possible for information to be forwarded easily between friends and colleagues. It also allowed Obama to connect with a younger generation that was often left out of politics.

By Election Day, Obama’s skill with the web was clear: he had over two million Facebook supporters, while McCain had 600,000. Obama had 112,000 followers on Twitter, and McCain had only 4,600.[57]

Are there any disadvantages to a presidential candidate’s use of social media and the Internet for campaign purposes? Why or why not?

The availability of the Internet and social media has moved some control of the message back into the presidents’ and candidates’ hands. Politicians can now connect to the people directly, bypassing journalists. When Barack Obama’s minister, the Reverend Jeremiah Wright, was accused of making inflammatory racial sermons in 2008, Obama used YouTube to respond to charges that he shared Wright’s beliefs. The video drew more than seven million views.[58] To reach out to supporters and voters, the White House maintains a YouTube channel and a Facebook site, as did the recent Republican Speaker of the House of Representatives, John Boehner.

Social media, like Facebook, also placed journalism in the hands of citizens: citizen journalism occurs when citizens use their personal recording devices and cell phones to capture events and post them on the Internet. In 2012, citizen journalists caught both presidential candidates by surprise. Mitt Romney was taped by a bartender’s personal camera saying that 47 percent of Americans would vote for President Obama because they were dependent on the government.[59] Obama was recorded by a Huffington Post volunteer saying that some Midwesterners “cling to guns or religion or antipathy to people who aren’t like them” due to their frustration with the economy.[60] More recently, as Donald Trump was trying to close out the fall 2016 campaign, his musings about having his way with women were revealed on the infamous Billy Bush Access Hollywood tape. These statements became nightmares for the campaigns. As journalism continues to scale back and hire fewer professional writers in an effort to control costs, citizen journalism may become the new normal.[61]

Another shift in the new media is a change in viewers’ preferred programming. Younger viewers like there to be humor in their news. In terms of TV, the popularity of The Daily Show with Trevor Noah, the Late Show with Stephen Colbert, and Full Frontal with Samantha Bee demonstrate that news, even political news, can win young viewers if delivered well.[62] Such soft news presents news in an entertaining and approachable manner, painlessly introducing a variety of topics. While the depth or quality of reporting may be less than ideal, these shows can sound an alarm as needed to raise citizen awareness (Figure 5.11).[63] Some young viewers also get their fun news from social media networks, such as TikTok, Twitter, and Instagram.

LINK TO LEARNING

Viewers who watch or listen to programs like John Oliver’s Last Week Tonight are more likely to be aware and observant of political events and foreign policy crises than they would otherwise be.[64] They may view opposing party candidates more favorably because the low-partisan, friendly interview styles allow politicians to relax and be conversational rather than defensive.[65] Because viewers of political comedy shows watch the news frequently, they may, in fact, be more politically knowledgeable than citizens viewing national news. In two studies researchers interviewed respondents and asked knowledge questions about current events and situations. Viewers of The Daily Show scored more correct answers than viewers of news programming and news stations.[66] That being said, it is not clear whether the number of viewers is large enough to make a big impact on politics, nor do we know whether the learning is long term or short term.[67]

GET CONNECTED!

Becoming a Citizen Journalist

Local government and politics need visibility. College students need a voice. Why not become a citizen journalist? City and county governments hold meetings on a regular basis and students rarely attend. Yet issues relevant to students are often discussed at these meetings, like increases in street parking fines, zoning for off-campus housing, and tax incentives for new businesses that employ part-time student labor. Attend some meetings, ask questions, and write about the experience on your Facebook page. Create a blog to organize your reports or use Storify to curate a social media debate. If you prefer videography, create a YouTube channel to document your reports on current events, or Tweet your live video using Periscope or Meerkat.

Not interested in government? Other areas of governance that affect students are the university or college’s Board of Regents meetings. These cover topics like tuition increases, class cuts, and changes to student conduct policies. If your state requires state institutions to open their meetings to the public, consider attending. You might be the one to notify your peers of changes that affect them.

What local meetings could you cover? What issues are important to you and your peers?

5.4 Regulating the Media

LEARNING OUTCOMES

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Identify circumstances in which the freedom of the press is not absolute

- Compare the ways in which the government oversees and influences media programming

The Constitution gives Congress responsibility for promoting the general welfare. While it is difficult to define what this broad dictate means, Congress has used it to protect citizens from media content it deems inappropriate. Although the media are independent participants in the U.S. political system, their liberties are not absolute and there are rules they must follow.

Media and the First Amendment

The U.S. Constitution was written in secrecy. Journalists were neither invited to watch the drafting, nor did the framers talk to the press about their disagreements and decisions. Once it was finished, however, the Constitution was released to the public and almost all newspapers printed it. Newspaper editors also published commentary and opinion about the new document and the form of government it proposed. Early support for the Constitution was strong, and Anti-Federalists (who opposed it) argued that their concerns were not properly covered by the press. The eventual printing of The Federalist Papers, and the lesser-known Anti-Federalist Papers, fueled the argument that the press was vital to American democracy. It was also clear the press had the ability to affect public opinion and therefore public policy.[68]

The approval of the First Amendment, as a part of the Bill of Rights, demonstrated the framers’ belief that a free and vital press was important enough to protect. It said:

“Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the government for a redress of grievances.”

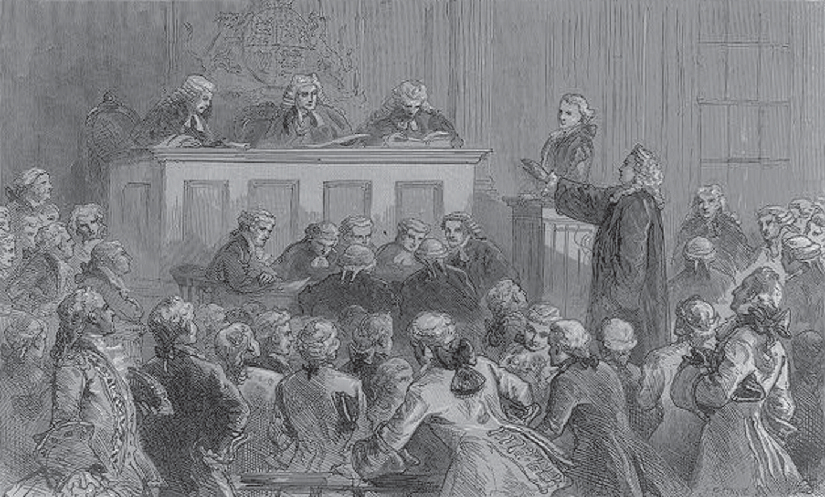

This amendment serves as the basis for the political freedoms of the United States, and freedom of the press plays a strong role in keeping democracy healthy. Without it, the press would not be free to alert citizens to government abuses and corruption. In fact, one of New York’s first newspapers, the New York Weekly Journal, began under John Peter Zenger in 1733 with the goal of routing corruption in the colonial government. After the colonial governor, William Cosby, had Zenger arrested and charged with seditious libel in 1735, his lawyers successfully defended his case and Zenger was found not guilty, affirming the importance of a free press in the colonies (Figure 5.12).

The media act as informants and messengers, providing the means for citizens to become informed and serving as a venue for citizens to announce plans to assemble and protest actions by their government. Yet the government must ensure the media are acting in good faith and not abusing their power. Like the other First Amendment liberties, freedom of the press is not absolute. The media have limitations on their freedom to publish and broadcast.

Slander and Libel

First, the media do not have the right to commit slander, speak false information with an intent to harm a person or entity, or libel, print false information with an intent to harm a person or entity. These acts constitute defamation of character that can cause a loss of reputation and income. The media do not have the right to free speech in cases of libel and slander because the information is known to be false. Yet on a weekly basis, newspapers and magazines print stories that are negative and harmful. How can they do this and not be sued?

First, libel and slander occur only in cases where false information is presented as fact. When editors or columnists write opinions, they are protected from many of the libel and slander provisions because they are not claiming their statements are facts. Second, it is up to the defamed individual or company to bring a lawsuit against the media outlet, and the courts have different standards depending on whether the claimant is a private or public figure. A public figure must show that the publisher or broadcaster acted in “reckless disregard” when submitting information as truth or that the author’s intent was malicious. This test goes back to the New York Times v. Sullivan (1964) case, in which a police commissioner in Alabama sued over inaccurate statements in a newspaper advertisement.[69] Because the commissioner was a public figure, the U.S. Supreme Court applied a stringent test of malice to determine whether the advertisement was libel; the court deemed it was not.

A private individual must make one of the above arguments or argue that the author was negligent in not making sure the information was accurate before publishing it. For this reason, newspapers and magazines are less likely to stray from hard facts when covering private individuals, yet they can be willing to stretch the facts when writing about politicians, celebrities, or public figures. But even stretching the truth can be costly for a publisher. In 2010, Star magazine published a headline, “Addiction Nightmare: Katie Drug Shocker,” leading readers to believe actress Katie Holmes was taking drugs. While the article in the magazine focuses on the addictive quality of Scientology sessions rather than drugs, the implication and the headline were different. Because drugs cause people to act erratically, directors might be less inclined to hire Holmes if she were addicted to drugs. Thus Holmes could argue that she had lost opportunity and income from the headline. While the publisher initially declined to correct the story, Holmes filed a $50 million lawsuit, and Star’s parent company American Media, Inc. eventually settled. Star printed an apology and made a donation to a charity on Holmes’ behalf.[70]

Classified Material

The media have only a limited right to publish material the government says is classified. If a newspaper or media outlet obtains classified material, or if a journalist is witness to information that is classified, the government may request certain material be redacted or removed from the article. In many instances, government officials and former employees give journalists classified paperwork in an effort to bring public awareness to a problem. If the journalist calls the White House or Pentagon for quotations on a classified topic, the president may order the newspaper to stop publication in the interest of national security. The courts are then asked to rule on what is censored and what can be printed.

The line between the people’s right to know and national security is not always clear. In 1971, the Supreme Court heard the Pentagon Papers case, in which the U.S. government sued the New York Times and the Washington Post to stop the release of information from a classified study of the Vietnam War. The Supreme Court ruled that while the government can impose prior restraint on the media, meaning the government can prevent the publication of information, that right is very limited. The court gave the newspapers the right to publish much of the study, but revelation of troop movements and the names of undercover operatives are some of the few approved reasons for which the government can stop publication or reporting.

During the second Persian Gulf War, FOX News reporter Geraldo Rivera convinced the military to embed him with a U.S. Army unit in Iraq to provide live coverage of its day-to-day activities. During one of the reports he filed while traveling with the 101st Airborne Division, Rivera had his camera operator record him drawing a map in the sand, showing where his unit was and using Baghdad as a reference point. Rivera then discussed where the unit would go next. Rivera was immediately removed from the unit and escorted from Iraq.[71] The military exercised its right to maintain secrecy over troop movements, stating that Rivera’s reporting had given away troop locations and compromised the safety of the unit. Rivera’s future transmissions and reporting were censored until he was away from the unit.

Media and FCC Regulations

LINK TO LEARNING

*Watch this video to learn about attempts to regulate media.

The liberties enjoyed by newspapers are overseen by the U.S. court system, while television and radio broadcasters are monitored by both the courts and a government regulatory commission.

The Radio Act of 1927 was the first attempt by Congress to regulate broadcast materials. The act was written to organize the rapidly expanding number of radio stations and the overuse of frequencies. But politicians feared that broadcast material would be obscene or biased. The Radio Act thus contained language that gave the government control over the quality of programming sent over public airwaves, and the power to ensure that stations maintained the public’s best interest.[72]

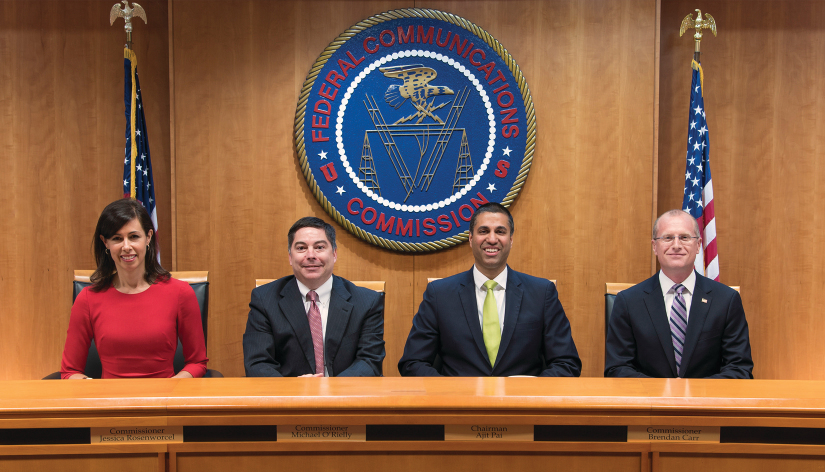

The Communications Act of 1934 replaced the Radio Act and created a more powerful entity to monitor the airwaves—a seven-member Federal Communications Commission (FCC) to oversee both radio and telephone communication. The FCC, which now has only five members (Figure 5.13), requires radio stations to apply for licenses, granted only if stations follow rules about limiting advertising, providing a public forum for discussion, and serving local and minority communities. With the advent of television, the FCC was given the same authority to license and monitor television stations. The FCC now also enforces ownership limits to avoid monopolies and censors materials deemed inappropriate. It has no jurisdiction over print media, mainly because print media are purchased and not broadcast.

LINK TO LEARNING

Concerned about something you heard or viewed? Would you like to file a complaint about an obscene radio program or place your phone number on the Do Not Call list? The FCC oversees each of these.

To maintain a license, stations are required to meet a number of criteria. The equal-time rule, for instance, states that registered candidates running for office must be given equal opportunities for airtime and advertisements at non-cable television and radio stations beginning forty-five days before a primary election and sixty days before a general election. Should WBNS in Columbus, Ohio, agree to sell Senator Marco Rubio thirty seconds of airtime for a presidential campaign commercial, the station must also sell all other candidates in that race thirty seconds of airtime at the same price. This rate cannot be more than the station charges favored commercial advertisers that run ads of the same class and during the same time period.[73] More importantly, should Fox5 in Atlanta give Bernie Sanders five minutes of free airtime for an infomercial, the station must honor requests from all other candidates in the race for five minutes of free equal air time or a complaint may be filed with the FCC.[74] In 2015, Donald Trump, when he was running for the Republican presidential nomination, appeared on Saturday Night Live. Other Republican candidates made equal time requests, and NBC agreed to give each candidate twelve minutes and five seconds of air time on a Friday and Saturday night, as well as during a later episode of Saturday Night Live.[75]

The FCC does waive the equal-time rule if the coverage is purely news. If a newscaster is covering a political rally and is able to secure a short interview with a candidate, equal time does not apply. Likewise, if a news program creates a short documentary on the problem of immigration reform and chooses to include clips from only one or two candidates, the rule does not apply.[76] But the rule may include shows that are not news. For this reason, some stations will not show a movie or television program if a candidate appears in it. In 2003, Arnold Schwarzenegger and Gary Coleman, both actors, became candidates in California’s gubernatorial recall election. Television stations did not run Coleman’s sitcom Diff’rent Strokes or Schwarzenegger’s movies because they would have been subject to the equal time provision. With 135 candidates on the official ballot, stations would have been hard-pressed to offer thirty-minute and two-hour time slots to all.[77] Even the broadcasting of the president’s State of the Union speech can trigger the equal-time provisions. Opposing parties in Congress now use their time immediately following the State of the Union to offer an official rebuttal to the president’s proposals.[78]

While the idea behind the equal-time rule is fairness, it may not apply beyond candidates to supporters of that candidate or of a cause. Hence, there potentially may be a loophole in which broadcasters can give free time to just one candidate’s supporters. In the 2012 Wisconsin gubernatorial recall election, Scott Walker’s supporters were allegedly given free air time to raise funds and ask for volunteers while opponent Tom Barrett’s supporters were not.[79] According to someone involved in the case, the FCC declined to intervene after a complaint was filed on the matter, saying the equal-time rule applied only to the actual candidates, and that the case was an instance of the now-dead fairness doctrine.[80] The fairness doctrine was instituted in 1949 and required licensed stations to cover controversial issues in a balanced manner by providing listeners with information about all perspectives on any controversial issue. If one candidate, cause, or supporter was given an opportunity to reach the viewers or listeners, the other side was to be given a chance to present its side as well. The fairness doctrine ended in the 1980s, after a succession of court cases led to its repeal by the FCC in 1987, with stations and critics arguing the doctrine limited debate of controversial topics and placed the government in the role of editor.[81]

The FCC also maintains indecency regulations over television, radio, and other broadcasters, which limit indecent material and keep the public airwaves free of obscene material.[82] While the Supreme Court has declined to define obscenity, it is identified using a test outlined in Miller v. California (1973).[83] Under the Miller test, obscenity is something that appeals to deviants, breaks local or state laws, and lacks value.[84] The Supreme Court determined that the presence of children in the audience trumped the right of broadcasters to air obscene and profane programming. However, broadcasters can show indecent programming or air profane language between the hours of 10 p.m. and 6 a.m.[85]

The Supreme Court has also affirmed that the FCC has the authority to regulate content. When a George Carlin skit was aired on the radio with a warning that material might be offensive, the FCC still censored it. The station appealed the decision and lost.[86] Fines can range from tens of thousands to millions of dollars, and many are levied for sexual jokes on radio talk shows and nudity on television. In 2004, Janet Jackson’s wardrobe malfunction during the Super Bowl’s half-time show cost the CBS network $550,000.

While some FCC violations are witnessed directly by commission members, like Jackson’s exposure at the Super Bowl, the FCC mainly relies on citizens and consumers to file complaints about violations of equal time and indecency rules. Approximately 2 percent of complaints to the FCC are about radio programming and 10 percent about television programming, compared to 71 percent about telephone complaints and 15 percent about Internet complaints.[87] Yet what constitutes a violation is not always clear for citizens wishing to complain, nor is it clear what will lead to a fine or license revocation. In October 2014, parent advocacy groups and consumers filed complaints and called for the FCC to fine ABC for running a sexually charged opening scene in the drama Scandal immediately after It’s the Great Pumpkin, Charlie Brown—without an ad or the cartoon’s credits to act as a buffer between the very different types of programming.[88] The FCC did not fine ABC.

The Telecommunications Act of 1996 brought significant changes to the radio and television industries. It dropped the limit on the number of radio stations (forty) and television stations (twelve) a single company could own. It also allowed networks to purchase large numbers of cable stations. In essence, it reduced competition and increased the number of conglomerates. Some critics, such as Common Cause, argue that the act also raised cable prices and made it easier for companies to neglect their public interest obligations.[89] The act also changed the role of the FCC from regulator to monitor. The Commission oversees the purchase of stations to avoid media monopolies and adjudicates consumer complaints against radio, television, and telephone companies.

An important change in government regulation of the press in the name of the fairness of coverage relates to net neutrality. Net neutrality rules were promulgated in 2015 by the Obama administration. These regulations required internet service providers to give everyone equal access to their services and disallowed biased charging of internet access fees. Early in the Trump Administration, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) reversed that course by throwing out the policy of net neutrality.[90] Later, the Trump administration challenged California's state law providing for net neutrality in court. The Biden administration dropped the lawsuit less than two weeks after taking office in 2021.[91] In March 2020, a group of tech companies petitioned the FCC to go a step further and formally reinstate net neutrality.[92]

FINDING A MIDDLE GROUND

Watch Dog or Paparazzi?

We expect the media to keep a close eye on the government. But at what point does the media coverage cross from informational to sensational?

In 2012, former secretary of state Hillary Clinton was questioned about her department’s decisions regarding the U.S. consulate in Benghazi, Libya. The consulate had been bombed by militants, leading to the death of an ambassador and a senior service officer. It was clear the United States had some knowledge that there was a threat to the consulate, and officials wondered whether requests to increase security at the consulate had been ignored. Clinton was asked to appear before a House Select Committee to answer questions, and the media began its coverage. While some journalists limited their reporting to Benghazi, others did not. Clinton was hounded about everything from her illness (dubbed the “Benghazi-flu”) to her clothing to her facial expressions to her choice of eyeglasses.[93] Even her hospital stay was questioned.[94] Some argued the expanded coverage was due to political attacks on Clinton, who at that time was widely perceived to be the top contender for the Democratic presidential nomination in 2016.[95] Republican majority leader Kevin McCarthy later implied that the hearings were an attempt to make Clinton look untrustworthy.[96] Yet Clinton was again brought before the House Select Committee on Benghazi as late as October 2015 (Figure 5.14).

This coverage should lead us to question whether the media gives us the information we need, or the information we want. Were people concerned about an attack on U.S. state officials working abroad, or did they just want to read rumors and attacks on Clinton? Did Republicans use the media’s tendency to pursue a target as a way to hurt Clinton in the polls? If the media gives us what we want, the answer seems to be that we wanted the media to act as both watchdog and paparazzi.

How should the press have acted in this case if it were behaving only as the watchdog of democracy?

Media and transparency

The press has had some assistance in performing its muckraking duty. Laws that mandate federal and many state government proceedings and meeting documents be made available to the public are called sunshine laws. Proponents believe that open disagreements allow democracy to flourish and darkness allows corruption to occur. Opponents argue that some documents and policies are sensitive, and that the sunshine laws can inhibit policymaking.

While some documents may be classified due to national or state security, governments are encouraged to limit the over-classification of documents. The primary legal example for sunshine laws is the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA), passed in 1966 and signed by President Lyndon B. Johnson. The act requires the executive branch of the U.S. government to provide information requested by citizens and was intended to increase openness in the executive branch, which had been criticized for hiding information. Citizens wishing to obtain information may request documents from the appropriate agencies, and agencies may charge fees if the collection and copying of the requested documentation requires time and labor.[97] FOIA also identifies data that does not need to be disclosed, such as human resource and medical records, national defense records, and material provided by confidential sources, to name a few.[98] Not all presidents have embraced this openness, however. President Ronald Reagan, in 1981, exempted the CIA and FBI from FOIA requests.[99] Information requests have increased significantly in recent years, with U.S. agencies receiving over 700,000 requests in 2014, many directed to the Departments of State and Defense, thus creating a backlog.[100] As FOIA requests have become institutionalized across the levels of the U.S. government, one challenge is the work created in responding to those requests.[101] For example, at the University of Oklahoma, two staff in the university counsel's office spend most of their time responding to FOIA requests about the university.

LINK TO LEARNING

Few people file requests for information because most assume the media will find and report on important problems. And many people, including the press, assume the government, including the White House, sufficiently answers questions and provides information about government actions and policies. This expectation is not new. During the Civil War, journalists expected to have access to those representing the government, including the military. But William Tecumseh Sherman, a Union general, maintained distance between the press and his military. Following the publication of material Sherman believed to be protected by government censorship, a journalist was arrested and nearly put to death. The event spurred the creation of accreditation for journalists, which meant a journalist must be approved to cover the White House and the military before entering a controlled area. All accredited journalists also need approval by military field commanders before coming near a military zone.[102]

To cover war up close, more journalists are asking to travel with troops during armed conflict. In 2003, George W. Bush’s administration decided to allow more journalists in the field, hoping the concession would reduce friction between the military and the press. The U.S. Department of Defense placed fifty-eight journalists in a media boot camp to prepare them to be embedded with military regiments in Iraq. Although the increase in embedded journalists resulted in substantial in-depth coverage, many journalists felt their colleagues performed poorly, acting as celebrities rather than reporters.[103]

The line between journalists’ expectation of openness and the government’s willingness to be open has continued to be a point of contention. Some administrations use the media to increase public support during times of war, as Woodrow Wilson did in World War I. Other presidents limit the media in order to limit dissent. In 1990, during the first Persian Gulf War, journalists received all publication material from the military in a prepackaged and staged manner. Access to Dover, the air force base that receives coffins of U.S. soldiers who die overseas, was closed. Journalists accused George H. W. Bush’s administration of limiting access and forcing them to produce bad pieces. The White House believed it controlled the message.[104] The ban was later lifted.

In his 2008 presidential run, Barack Obama promised to run a transparent White House.[105] Yet once in office, he found that transparency makes it difficult to get work done, and so he limited access and questions. In his first year in office, George W. Bush, who was criticized by Obama as having a closed government, gave 147 question-and-answer sessions with journalists, while Obama gave only 46. Even Helen Thomas, a long-time liberal White House press correspondent, said the Obama administration tried to control both information and journalists (Figure 5.15).[106]

The Trump administration had an especially bumpy relationship with the news media. In part, this had to do with Trump's penchant for using Twitter, instead of news briefings, to get his thoughts out to the public. The repeated line from the former president that news media could not be trusted, which he called "fake news," added insult to injury. The prickly relationship also resulted from reduced use of traditional press gaggles and excluding some media outlets, such as CNN, when tempers flared.

While some may have expected the Biden administration to undertake a complete reversal from the Trump White House, the first few months demonstrated that presidents' overall relationships with the press may have evolved. A number of news outlets and media commentators noted the lack of a formal press conference for months after Biden took office. However, he did frequently provide comments and answer questions during other occasions.[107]

Because White House limitations on the press are not unusual, many journalists rely on confidential sources. In 1972, under the cloak of anonymity, the associate director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, Mark Felt, became a news source for Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, political reporters at the Washington Post. Felt provided information about a number of potential stories and was Woodward’s main source for information about President Richard Nixon’s involvement in a series of illegal activities, including the break-in at Democratic Party headquarters in Washington’s Watergate office complex. The information eventually led to Nixon’s resignation and the indictment of sixty-nine people in his administration. Felt was nicknamed “Deep Throat,” and the journalists kept his identity secret until 2005.[108]