19 Encouraging Students to Try Out New Learning Strategies

Lynn Meade

Teaching Students How to Learn: Strategies for Success

in which their job is to change the human brain every day.”

David Sousa

We want our students to put in the hard work of learning, and we want them to use strategies that are known to work. This chapter offers strategies you can share with your students to help with the “work” of learning on the road to becoming self-regulated learners.

In this chapter, you will learn.

- How to coach students to use the Pomodoro technique.

- How cell phones can be a hindrance to learning.

- Why distributed practice works and why it is better than cramming.

- How active recall creates deep learning.

- Why sleep impacts learning.

Teach Students the Pomodoro Technique

Do you know what the Italian word for tomato is? It is “pomodoro.” The originator of the Pomodoro Technique, Francesco Cirillo, would use a timer shaped like a tomato to help himself study for concentrated amounts of time. The beauty of this technique lies in its simplicity: focused work periods followed by intentional breaks.

Here’s the basic framework:

- Set a timer for 25 minutes.

- Focus completely on your work.

- If distracting thoughts arise, quickly jot them down on paper and return to your task.

- When the timer rings, take a 5-minute break.

- After completing four cycles, take a longer 15-30 minute break.

The goal is to maintain focus for a set period. What makes this method particularly effective is its approach to distractions. Rather than fighting against wandering thoughts, students acknowledge them by quickly writing them down, then return to their work. During breaks, students can address these noted thoughts or tasks.

There are many excellent videos on the topic, but I picked this one because it shows meaningful variations of the technique. It is also fast-moving and easy to understand, making it a great video to share with students.

Encourage Students to Move Their Cell Phones Out of The Room

Many things can distract from focus, and one of those things is a cell phone. It is likely no surprise that students who have their cell phones out during class have lower comprehension and lower test scores, but you may not know that having a cell phone in visual range while studying can also impede learning. Researchers at the University of Texas discovered that even a cell phone that is turned off can impair cognitive performance.

Researchers divided 800 smartphone users into three groups:

- Phones placed on the desk

- Phones stored in bags in the room

- Phones kept in another room

All phones were turned off, yet the results were striking. The physically closer students were to their phones, the more their working memory and fluid intelligence suffered. In other words, having your phone in your backpack that is in the room, can still impact learning. Researchers dubbed this the “brain drain hypothesis” – an apt description of how phones silently sap cognitive resources. The more a student was dependent on their phone, the more it hurt their learning. Two roommates I coached had a solution: they would give each other their phones during their set study times. One told me, “It may sound funny, but we found that it works!”

Practical Implementation

When introducing the Pomodoro Technique to your students, connect it with cell phone research. Encourage them to:

- Choose a dedicated study space

- Move their phone (and smart watches) to another room before starting

- Use a simple timer (not their phone) for Pomodoro sessions

- Keep a small notepad for capturing distracting thoughts

When students combine the Pomodoro Technique with mindful phone placement, it can create an environment that truly supports deep learning and sustained focus.

Speaking of Cell Phones and Focus

There are apps that students can use to help with focus.

Teach Students Effective Learning Strategies: Beyond Cramming

If you know something, or if you have stored information about an event from the distant past, and never use

that information, never think of it, your brain is functionally equivalent to that of an otherwise identical brain

that does not “contain” that information.

—Endel Tulving (1991)

“Cramming works for me!” It’s a common refrain among students. At first glance, cramming might seem to work. After all, most students can point to at least one success story where cramming helped them pass a test. While students might temporarily hold information for a test, that knowledge typically vanishes shortly after. This becomes painfully evident when they need to access this material later and find that they have to learn the material all over again.

The Power of Distributed Practice

Neuroscience research demonstrates that distributed retrieval practice creates stronger, more durable learning outcomes. Spaced repetition involves the repeated review of previously learned material at various intervals. A comprehensive meta-analysis of 55 studies found that 78% showed significant benefits for learners using spaced repetition techniques.

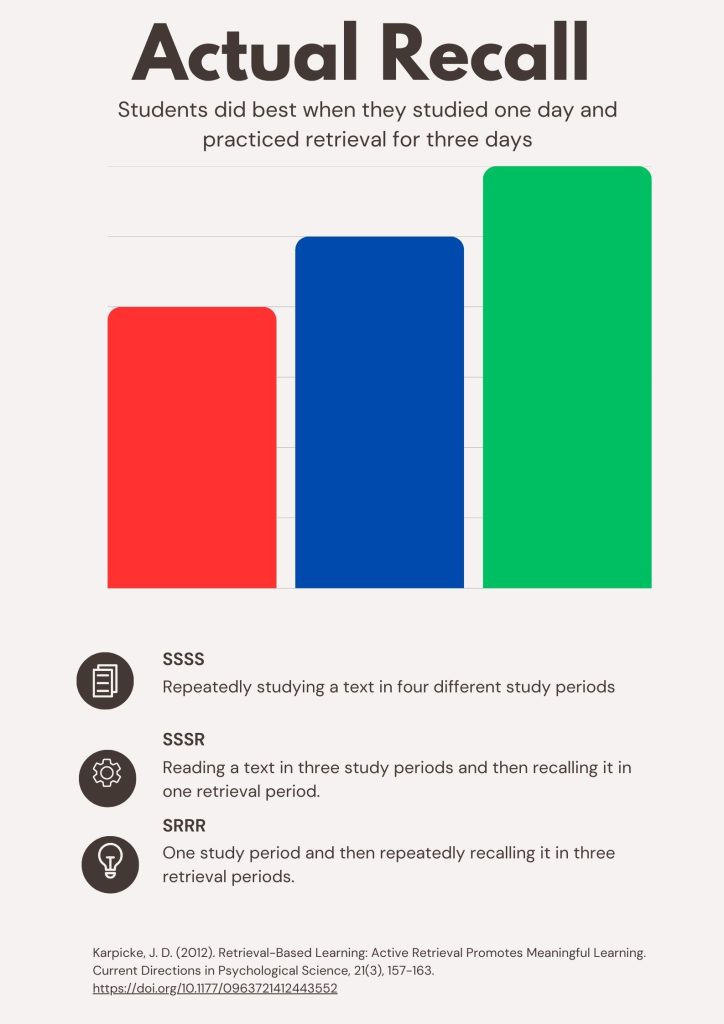

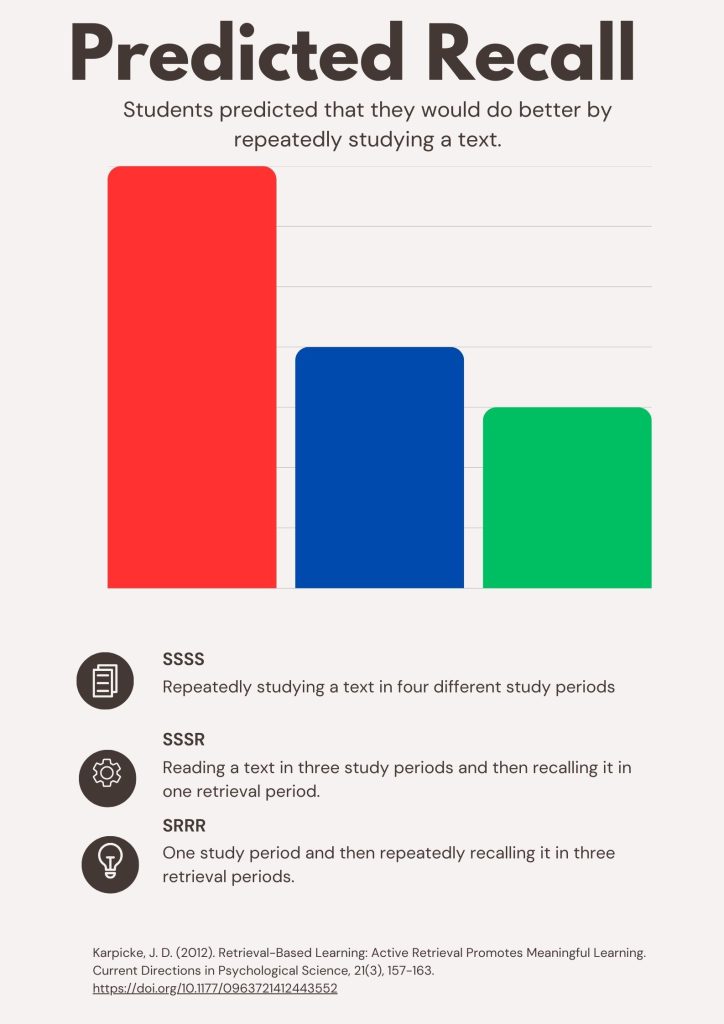

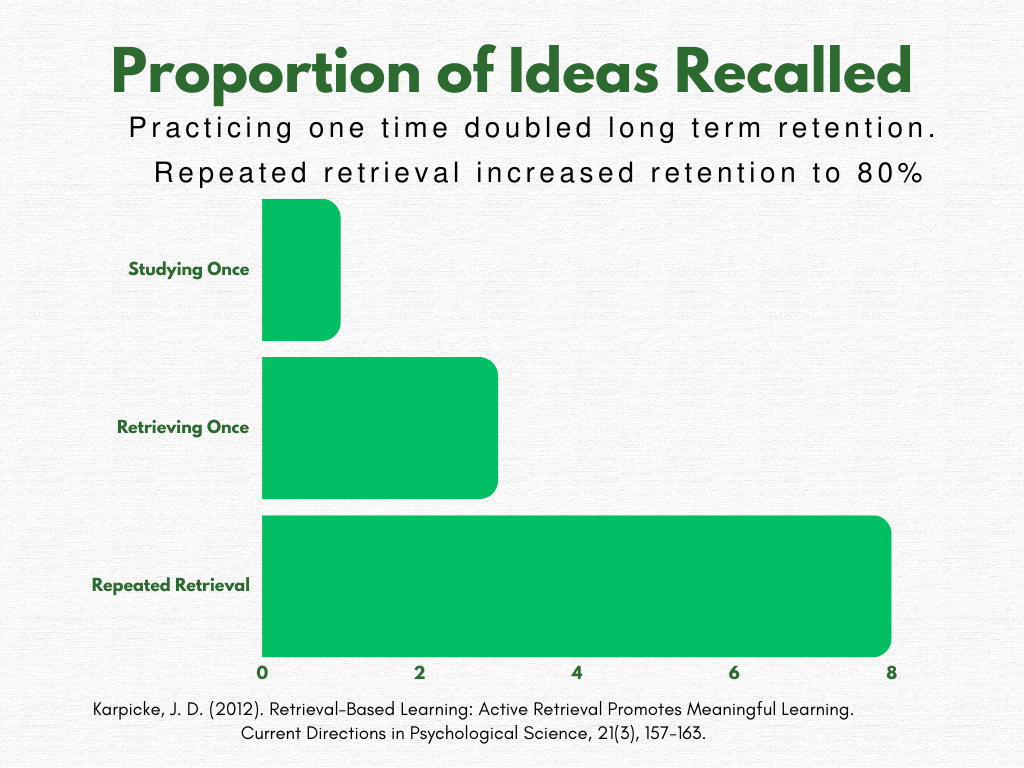

Distributed practice can improve skill development and enhance student attitudes toward learning. When students begin to succeed through consistent practice, they develop more favorable attitudes toward challenging courses. After all, it is easier to like a class and think that class is worthwhile when you are not failing it. Karpicke revealed that students who had repeated retrieval of information showed up to an 80% increase in the proportion of ideas recalled, reinforcing the time-tested adage that “practice makes permanent.”

Active Recall: The Key to Deep Learning

Perhaps the most crucial insight about learning is this: Retention happens during retrieval, not during initial exposure. Learning occurs when students actively reconstruct material from memory, discuss what they’ve learned, and apply their knowledge to new situations. This is called active recall. Active recall may look like many things but it always involves intentionally reconstructing what they have learned. It is that reconstruction of the information that actively enhances learning. This type of work closely parallels the world outside of college where students will have to apply their knowledge in real-time.

If you think of your brain as a muscle, making it work to find a piece of information is training that muscle to get stronger and find the information more easily in the future. Research shows that active recall can improve long-term retention by two to three times compared to passive review methods. The more you retrieve the information, the more you learn.

The more you practice recalling the information, the more it becomes part of your long-term memory. Knowing the answers feels good! This is why most studies report one of the benefits of using active recall with distributed practice is an improved sense of self-efficacy.

Active recall can be …

- Trying to recall the material and then going back and studying what you don’t know.

- Answering questions about a topic (especially those without multiple-choice answers).

- Finding old math tests with similar problems and practicing solving them.

- Teaching the concept to others.

- Practicing a speech without notes.

- Writing explanations in your own words.

- Talking through answers in a study

| Active Recall Works Better Than… |

Rereading | Rereading is often passive, and students tend to look at the words without really thinking about what they mean. |

| Highlighting the reading | Highlighting often takes place without really thinking about the material. Most studies show no benefit to highlighting. | |

| Creating concept maps | While this technique can become a type of active recall as one recreates or designs new maps from memory, it is not considered a very effective study strategy and is often used poorly. | |

| Re-listening to recorded lectures | This tends to be a passive activity, and often times, the lecture becomes background noise. It can be useful to revisit content where one struggles. | |

| Re-reading notecards | While looking at notecards can help, this is enhanced in multiple ways. It is better to create the notecards by summarizing the information. When you use your notecards, say the concepts as if you were teaching that idea to someone.

|

|

Karpicke, J. D. (2012). Retrieval-Based Learning: Active Retrieval Promotes Meaningful Learning. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 21(3), 157-163.Dunlosky, J., Rawson, K. A., Marsh, E. J., Nathan, M. J., & Willingham, D. T. (2013). Improving Students’ Learning With Effective Learning Techniques: Promising Directions From Cognitive and Educational Psychology. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 14(1), 4-58. |

||

Research has consistently shown that retrieval practice enhances memory retention more effectively than re-studying. In one notable study, students who engaged in retrieval practice outperformed those who created concept maps or participated in long study sessions, despite believing these latter methods would be more effective.

Pause and let that sink in a minute. Students thought one method was working, but when tested, that wasn’t true.

Refer to the study for details on these charts.

“You can’t short-change your brain of sleep and still learn effectively.”

Matthew Walker, Neuroscientist

Sleep Helps You Learn

By the end of the week, my desk is a complete mess. I often come in from class and pile extra handouts, lecture notes, and the roll sheet in a not-so-neat way. It is often tossed wildly on the corner of my desk. I’m off to a meeting with more handouts and more notes and then I add more to the pile. If you ask me on Thursday to find Monday’s handout, it might take me a minute to get through the pile. Every Monday, I come to the office early and I neatly file my papers and put them into their proper spots. I type up my meeting notes and consolidate similar topics. If something is important, I write a sticky note and put it on my computer so I won’t forget.

This is not really about me and my messy desk, it is about people and their messy minds. All day, we collect ideas, experiences, and memories and dump them hastily on the desk or in our minds. It is only when we sleep (specifically the final stages of sleep) that we organize those ideas in a way that we can access them. Sleep helps the parts of your brain associated with facts about the world and episodic events. When we don’t sleep and file the information, much of the information is lost.

Not only does sleep organize the materials and “file” them into long-term memory, but without sleep, the desk is so messy that you might not be able to pile any more information on it. It will just fall off on the floor (that did happen to me and my desk once). In other words, if you don’t file the old information, it can prevent you from taking in new information.

Interestingly enough, because of the filing aspect of sleep, it is better to study before going to bed rather than getting up early to study. That sleep allows the information to become a long-term memory.

Sleep is the key to having a brain that is ready to learn.

“We not only need sleep after learning to consolidate what we’ve learned,

but we also need to be rested before learning,

so that we can recharge and soak up information the next day.”

Matthew Walker

Watch this 2-minute video clip from Dr. Lila Landowski from her TED talk, “Six Secrets to Learning Faster, Backed by Neuroscience,”” on the connection of sleep and learning. Consider sharing this with your students.

Supporting Student Success

Coaches play a crucial role in helping students become self-regulated learners. By teaching these evidence-based techniques and explaining why they work, we empower students to take control of their learning journey. In this chapter, you learned strategies based on science that enhance learning. You learned about the Pomodoro technique and the advantages of distributed practice. Finally, you learned about how sleep impacts learning. To be a self-regulated leader, students need a plan on how to reach their learning goal and they need strategies on how to accomplish that.

Key Takeaways

- Learning is work but learning how to learn is a valuable investment in one’s future.

- The Pomodoro technique consists of focused work periods followed by intentional breaks.

- A cell phone that is in view, even if it is turned off can impair cognitive performance.

- Distributed retrieval practice– also known as spaced repetition–creates stronger, more durable learning outcomes.

- Spaced repetition involves the repeated review of previously learned material at various intervals.

- Retention happens during retrieval, not during initial exposure.

- Learning occurs when students actively reconstruct material from memory, discuss what they’ve learned, and apply their knowledge to new situations.

- Sleep is the key to having a brain that is ready to learn.

- It is during sleep that short term memories turn into long term memories. Without sleep, we do not organize new information making it easy to get lost. It also makes it hard to learn new things.

Downloadable Resources

Karpicke, J. D. (2012). Retrieval-Based Learning: Active Retrieval Promotes Meaningful Learning. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 21(3), 157-163.

Dunlosky, J., Rawson, K. A., Marsh, E. J., Nathan, M. J., & Willingham, D. T. (2013). Improving Students’ Learning With Effective Learning Techniques: Promising Directions From Cognitive and Educational Psychology. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 14(1), 4-58.

How to Study Less and Remember More: Effective Learning Techniques from Psychology Research fromUC SanDiego Psychology Department

References

Benson, W. L., Dunning, J. P., & Barber, D. (2022). Using distributed practice to improve students’ attitudes and performance in statistics. Teaching of Psychology, 49(1), 64-70.

Buzsáki, G., Girardeau, G., Benchenane, K., Wiener, S., & Zugaro, M. (2009). Selective suppression of hippocampal ripples impairs spatial memories. Nature Neuroscience, 12, 1222-1223.

Cepeda, N. J., Pashler, H., Vul, E., Wixted, J. T., & Rohrer, D. (2006). Distributed practice in verbal recall tasks: A review and quantitative synthesis. Psychological Bulletin, 132(3), 354-380.

Chen, Q., Zheng, Y., Moeyaert, M., & Bangert-Drowns, R. (2025). Mobile multitasking in learning: A meta-analysis of effects of mobile-phone distraction on young adults’ immediate recall. Computers in Human Behavior, 162, Article 108040.

Doyle, T. (2008). Helping students learn in a learner-centered environment. Stylus.

Doyle, T., & Zakrajsek, T. (2019). The new science of learning (2nd ed.). Stylus.

Dunlosky, J., Rawson, K. A., Marsh, E. J., Nathan, M. J., & Willingham, D. T. (2013). Improving Students’ Learning With Effective Learning Techniques: Promising Directions From Cognitive and Educational Psychology. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 14(1), 4-58.

Feng, K., Zhao, X., Liu, J., Yang, L., Liu, X., Ma, X., Liu, J., Li, X., & Luo, Y. (2019). Spaced learning enhances episodic memory by increasing neural pattern similarity across repetitions. Journal of Neuroscience, 39, 5351-5360.

Glass, A. L., & Kang, M. (2018). Dividing attention in the classroom reduces exam performance. Educational Psychology, 39(3), 395-408.

Howard, P. (2014). The owner’s manual for the brain: The ultimate guide to mental performance at all ages (4th ed.). William Morrow.

How to ADHD. (2021, February 11). What is a Pomodoro and how can it help with ADHD [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3FjIuPMQzxo

Kakitani, J., & Kormos, J. (2024). The effects of distributed practice on second language fluency development. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 46(3), 770-794.

Karpicke, J. D. (2012). Retrieval-based learning: Active retrieval promotes meaningful learning. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 21(3), 157-163.

Karpicke, J. D., & Blunt, J. R. (2011). Retrieval practice produces more learning than elaborative studying with concept mapping. Science, 331, 772-775.

Kelley, P., & Whatson, T. (2013). Making long-term memories in minutes: A spaced learning pattern from memory research in education. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 7, Article 589.

Landowski, L. (2023, May). Six secrets to learning faster, backed by neuroscience [Video]. TEDx Talks.

Marinelli, J. P., Hwa, T. P., Lohse, C. M., & Carlson, M. L. (2022). Harnessing the power of spaced repetition learning and active recall for trainee education in otolaryngology. American Journal of Otolaryngology, 43(5), Article 103511.

Nilson, L. B. (2013). Creating self-regulated learners: Strategies to strengthen students’ self-awareness and learning skills. Stylus.

Rohrer, D., & Pashler, H. (2007). Increasing retention without increasing study time. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 16(4), 183-186.

Schraw, G. (1998). Promoting general metacognitive awareness. Instructional Science, 26(1-2), 113-125.

Sousa, D. (2011). How the brain learns (4th ed.). Corwin.

Study Lab. (2021). Pomodoro technique [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GMi-wvDYJnY

Sung, J. (2023, December 13). Ultimate study technique tier list (Learning coach edition) [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WkjVaMDheJ4

Sung, J. (2023, December 20). How I upgrade the most popular study techniques [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YyMA9RwAcGE

Thornton, B., Faires, A., Robbins, M., & Rollins, E. (2014). The mere presence of a cell phone may be distracting: Implications for attention and task performance. Social Psychology, 45(6), 479-488.

Trumble, E., Lodge, J., Mandrusiak, A., & Forbes, R. (2023). Systematic review of distributed practice and retrieval practice in health professions education. Advances in Health Sciences Education: Theory and Practice, 29(2), 689-714. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-023-10274-3

Walker, M. P., & Robertson, E. M. (2016). Memory processing: Ripples in the resting brain. Current Biology, 26(6), 239-241.

Ward, A. F., Duke, K., Gneezy, A., & Bos, M. W. (2017). Brain drain: The mere presence of one’s own smartphone reduces available cognitive capacity. Journal of the Association for Consumer Research, 2(2), 140-154.

AI acknowledgment: This work was written by the author in its entirety. Claude AI and Chatgpt were used to refine some of the wording and suggest stronger headings. Claude AI was also used to proofread the reference page.

Bonus Features

There are so many useful videos on how to study, it can feel overwhelming. In this chapter, I wanted to pick just a few strategies that coaches are in a position to teach students. I wanted to hit them in enough detail that you could talk about them and easily follow up with your students about them.

In researching for this chapter, I found many useful items.

Landowski, L. (May 2023). Six Secrets to Learning Faster, Backed by Neuroscience. TedxTalks

Sung, J. (December 13, 2023). Ultimate Study Technique Tier List (Learning Coach Edition)

Superior

- Sleep: – Crucial for memory consolidation. – Sleep deprivation harms cognitive performance.

- Space Repetition: – Fundamental principle, advantageous. – Misuse due to rapid forgetting rate. –

A

- Pomodoro Technique: – Easy starter technique, aids focus. – Quick effectiveness. Aids focus and flow, can be optimized by adjusting break times.

- Practice Papers: – Effective for retrieval and knowledge gap identification. – Generally well-used

- Feynman Technique (Self-Explanation Refinement): – Good for gap finding, time-efficient. – Solid method

- Active Recall: – Effective for memory recall. – Limited by users’ knowledge of techniques.

B

- Pre-study: – Common method before main learning event. – Often of mixed effectiveness.

- Mnemonics: – Memory aid technique, potential for power. – Often underused or misapplied.

- Cornell Note Taking: -Difficult to do wrong, limited benefits even when done right.

C

- Brain Dumps: – Equivalent to blurting, limited benefits. – Time-consuming, often not high-quality.

- Summary Pages: – Effective but often underutilized. – Can be enhanced for better results.

- Mind Maps: – Often used ineffectively, similar to linear notes. – Requires correct technique for significant benefits.

D

- Flash Cards: – Highly effective when used right. – Often misused, potential for improvement.

- Watching Videos/Lectures: – Broad but low-yield technique. – Misuse common, often ineffective.

D–

- Rereading and Highlighting: – Generally ineffective, low benefit. – Hard to make work effectively.

Sung, J. (December 20, 2023). How I Upgrade the Most Popular Study Techniques. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YyMA9RwAcGE

Media Attributions

- david-matos-xtLIgpytpck-unsplash © David Mathos is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- eddy-billard-M5UD_FyuDl8-unsplash © Eddy Billard

- no-revisions-UhpAf0ySwuk-unsplash (1) © No revisions is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Proportion of Ideas Recalled

- Cream Modern Business Sales Bar Chart Infographic Poster

- Cream Modern Business Sales Bar Chart Infographic Poster (1)

- kate-stone-matheson-uy5t-CJuIK4-unsplash © Kate Stone Matheson is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license