7 Coaching Students to Use Design Thinking for Wicked Problems

Lynn Meade

The Crooked Path Full of Detours

How did you end up here? Yes, I’m talking to you, the reader. How did you end up coaching students? Is this where you imagined you would be 5 years ago? Is it where you imagined you would be 10 years ago? Are you chasing the same dreams you chased when you were eighteen? I would imagine that most of you are not exactly where you imagined.

My mother recently showed me a poem that I wrote when I was in kindergarten. “When I grow up, I want to be a nurse, and I will carry a big white purse.” (Nice rhyme, hunh?) My plans for my future changed when I realized that nurses had to clean up gross things. When I was twelve, I heard about King Tut, and I was determined to be an archeologist. That was the dream until I learned that I might be outside in uncomfortable weather with little paint brushes dusting off rocks. No, thank you.

I entered college as a first-generation college student doing the only logical thing according to my dad–business. I hated it. It wasn’t until I was forced by my general education requirements to take communication that I found something I truly liked. Up to that time, I didn’t even know communication was something you could study. That change created some interesting identity issues. On one hand, I found a major that I loved; on the other, I felt like I was letting down my family. Even more, I had made friends in my management classes and enjoyed visiting with them and now we wouldn’t have classes together anymore.

What’s the point?

Just like us, students often change their minds, change their majors, and change the way they see the world–they take detours. One of those changes frequently has to do with changing their major. It likely comes as no surprise to you that according to the National Center for Education Statistics, within three years of initial enrollment, about 30 percent of undergraduates changed their major at least once.

Why the change? Here is what students say:

- Difficulty of course material

- Life changes

- Better career opportunities

- Parental influence

- Peer discussion

- Advisor recommendations

What seems like just a change of major can mean so much more. Let’s look at the challenges students face when making transitions, especially those involving college decisions.

Nancy Schlossberg, a professor emeritus of counseling psychology at the University of Maryland, suggested that our students are encountering many transitions from home to college, from dorm to apartment, from hometown friends to college friends, and on top of that many are transitioning from one major to another. There is a lot of stress and uncertainty in times of change and transition.

She points out that self-identity is often linked to a major. When students meet other students one of the common questions is “What’s your major?” When they start a new class, the teacher asks them to “Tell us your name and your major.” When their family and coworkers ask about college, they ask, “What’s your major?”

For many students, a major is not what they study, it feels like who they are.

Furthermore, their relationships are often linked to their majors–they take classes with friends in their major and may have study partners with others in their major. They may be in a major to make a parent happy. Changing majors can mean changing friends. Changing majors can mean different support, different resources, and a different way of thinking about oneself.

Transitions can be hard.

Consider these students’ statements

-

- It was terrifying, of course. As a freshman, wanting to switch your major right away is terrifying.

- Navigating this change is “the biggest moment of uncertainty” in my college career. **

- I was very scared during that time just because I’m the type of person who always likes to have things planned out… I didn’t know what specific outcome I was going to have, so I was struggling a little bit to stay motivated, because I was just really scared and trying to figure out what it was exactly that I wanted to do.

When students are experiencing life transitions whether it is a change of major or a change of roommate, they can feel scared. Supporting our students through these types of transitions is important. Helping them see the growth that happens when someone decides to take a new path can help them feel empowered.

This is where design thinking comes in.

Design Thinking: A Powerful Approach to Life’s Wicked Problems

Design thinking is a mindset. It is a way to think about life’s detours. It’s a way of dealing with life’s wicked problems. Wicked problems are those problems that have no single correct answer but rather multiple potential solutions.

The ultimate wicked problem facing college students may be, “What should I do with my life?”

Ask About Identities

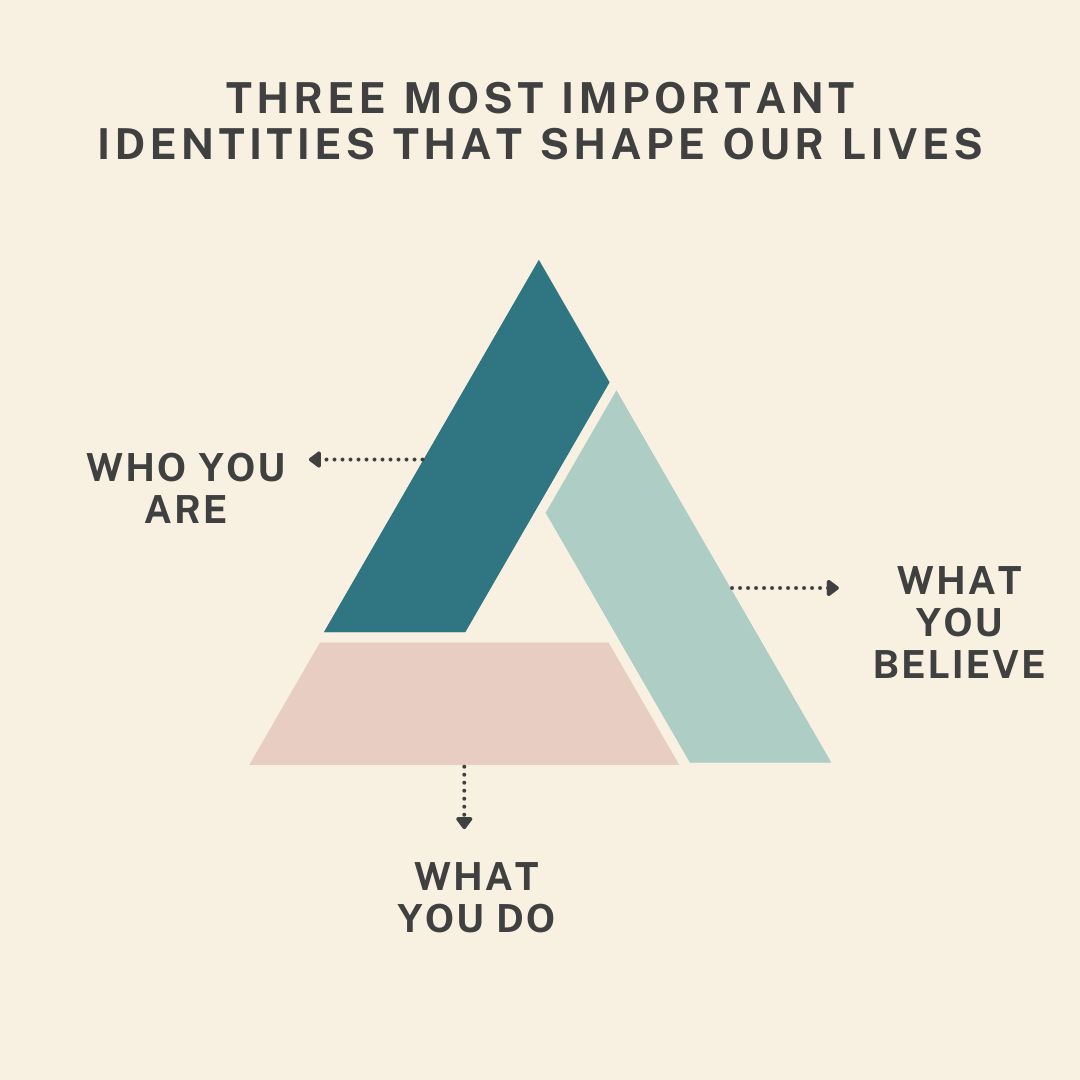

To help students reflect on the wicked problem of “what should I do with my life”, it is helpful to guide them to consider the three important identities that shape their lives: Who they are, what they believe, and what they do. Talk with your students about these and ask, “How do those align?”

Ask About Their Why

Another question to help them think about the wicked problem of life is to ask them, “What is Your Why?” This powerful question can lead to contemplation and great conversations about what matters to them, what motivates them, and may help point to what majors might be best for them.

Exercises

Here are some other questions to get students thinking:

- What is your why?

- Why are you here?

- What is your theory of work?

- What is all this for?

- What’s work in service of?

Brainstorm

Once they have considered their identity and motivation, you can help them brainstorm ideas. There’s no one-size-fits-all answer, and the “right” path varies greatly from person to person. After all, we know there are multiple right paths (and right majors) that can lead to a happy life and we need to help them imagine many futures for themselves.

Our role is to encourage curiosity and exploration rather than rushing to definitive answers.

Robust brainstorming is key.

Exercises for Brainstorming

Helping students navigate the many paths is an important role of coaches. The University of Arkansas has Challenge Cards that we can share with our students to help them think about possibilities. Challenge cards reframe the conversation from “What should I major in” and “What job should I pursue” to “What challenges interest me?”

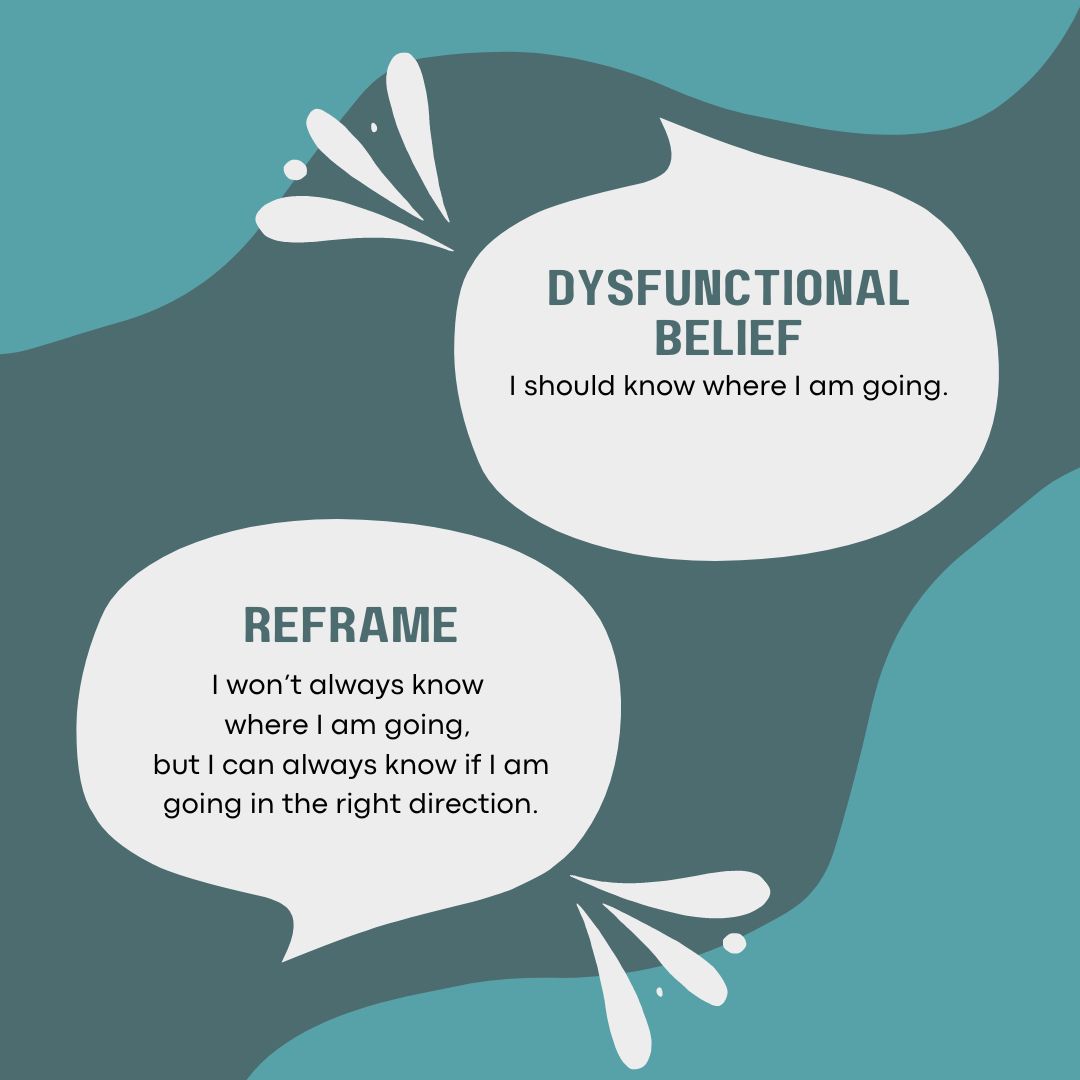

Reframing Dysfunctional Beliefs

Another aspect of design thinking that applies to coaching conversations is to help them reframe dysfunctional beliefs. Sometimes in life, we get stuck because we ask the wrong questions. Sometimes we start with dysfunctional beliefs. As coaches, we can help our students to reframe things and broaden their ideas. By helping them to shift perspective, we can often uncover new insights and possibilities and help our students get unstuck. For example, encourage students to stop asking, “What do I want to do” but rather “Who do I want to be?”

Many dysfunctional beliefs can cause students to get stuck, but I want to focus on three of the most common ones that you will encounter in coaching and offer suggestions on how you can help.

Check out Designing Your Life: How to Build a Well-Lived, Joyful Life for more dysfunctional beliefs.

Dysfunctional Belief: I should know where I’m going!

Reframe: I won’t always know where I’m going – but I can always know whether I’m going in the right direction.

Coaches’ Role: We can coach students to take classes that align with their interests and values. Staying true to your values is more important than getting the right degree.

Dysfunctional Belief: I need to figure out my best possible life, make a plan, and then execute it.

Reframe: There are multiple great lives (and plans) within me, and I get to choose which one to build my way forward next.

Coaches’ Role: Coach students that there are many great lives within them. If they get stuck, help them brainstorm different possibilities. This can be particularly helpful to discuss if they change majors because of struggles with tough courses.

Dysfunctional Belief: Your degree determines your career.

Reframe: Three-quarters of all college graduates don’t end up working in a career related to their majors.

Coaches’ Role: Sometimes, students worry they will pick the wrong degree. Helping them see that there are many possibilities available can relieve that pressure.

When we take the time to listen to students, we can identify which dysfunctional beliefs they may need to reconsider.

Exercises for Students Who Want to Invest More Time in Life Design

To help students brainstorm and to consider rethinking dysfunctional beliefs, the Stanford Design Your Life website has worksheets. These take time and involve multiple conversations, but for some students that time and effort might be just what they need to get unstuck. You can use these to help your students imagine alternative futures. These are called Odyssey Plans.

These worksheets ask students to imagine three different lives. This activity helps them use creative brainstorming to move from a stuck mindset to one that sees different possibilities.

Life 1: The story you tell (to your advisor/ parents, friends) today

Life 2: The life you might pursue if Life 1 was no longer an option

Life 3: The wild idea: your basic needs are assured to be met – no constraints

Life Prototyping

Prototyping is often thought of as an engineer building a model and testing the design. We can’t build a model of our lives to test, but we can prototype our lives.

What does life prototyping look like? It means you test out conversations and you test out experiences. A prototyped conversation can mean finding someone doing what you want to do and talking to them. Because they are living a life similar to what you want, you can learn from them. In essence, you can test ideas and imagine what your life would be like if you did the same.

A prototyped experience means you try out something. That might mean job shadowing, interning, or even volunteering. This gives you a chance to have a felt experience–a lived experience is the ultimate form of prototyping.

Exercises

Looking for ways to help your students prototype? Check out these resources

Career Services

- Search for Internships at the University of Arkansas

- Search for Internship Opportunities – Fulbright College of Arts and Sciences

Volunteering

- The University of Arkansas Volunteer Action Center can help with volunteering opportunities.

Key Elements in Using Design Thinking in Life Design

-

- Brainstorming Multiple Options: Encourage students to generate a range of potential career paths or life directions. The goal is to think broadly and creatively.

- Reframing: Teach students to look at their challenges from different angles. For college students, this might mean shifting from “How do I get a high-paying job?” to “How can I create a fulfilling career that aligns with my values?”

- Prototyping and Experimentation: Guide students to test different options through internships, informational interviews, or job shadowing. These “low-stakes experiments” can provide valuable insights and help refine their choices. If they are thinking of a change of major, have them go and talk to a professor in that department. If they are thinking about moving towards a particular career, encourage them to do an informational interview with someone who had that job.

For more on life design read Designing Your Life: How to Build a Well-Lived, Joyful Life by Burnett and Evans and watch Stop Pondering and Start Prototyping and Five Steps to Designing the Life that you Want.

In conclusion, the path from college to career is rarely straight or predictable. For our students, the process can be both exciting and stressful. By introducing design thinking principles, we give our students strategies for dealing with the uncertainty of life’s “wicked problems.” Helping students brainstorm and reframe helps them manage their mindset and prototyping helps them test those ideas. As coaches, our role is not to provide all the answers, but to guide students to ask better questions that lead to better mindsets that help them find their path. This mindset equips them for more than just picking a career path, it equips them with the skills they need to navigate life’s many wicked problems.

Key Takeaways

- Students struggle with life transitions such as making decisions about majors and careers.

- Wicked problems are those problems that have no one right answer like, “What should I do with my life?”

- Design thinking has been applied to wicked problems of life design.

- Coaches can ask, “What is your why?” to help students think differently about life design.

- Brainstorming can help think of multiple possibilities that lead to a happy life.

- Reframing dysfunctional beliefs can help to have better conversations about life design.

- Prototyping conversations and prototyping experiences are ways to test out ideas about majors and careers.

References

Astorne-Figari, C. and Speer, J.D. (2019). Are changes of major major changes? The roles of grades, gender, and preferences in college major switching. Economics of Education Review 70 p 75-93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2019.03.005

Burnett, B., & Evans, D. (2016). Designing your life: How to build a well-lived, joyful life. Knopf.

Burnett, B. Five Steps to Designing the Life You Want. You Tube

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SemHh0n19LA

Burnett, B. (2021). How to use design thinking to create a happier life for yourself. Ideas.Ted.com

Dennis Learning Center (March, 2023). Academic coach uses design thinking to guide students. https://ehe.osu.edu/news/listing/academic-coach-uses-design-thinking-guide-students

The Designing Your Life Story. https://designingyour.life/the-dyl-story/

Doyle, T., & Zakrajsek, T. (2019). The new science of learning (2nd ed.). Stylus.

Dweck, C. S. (2006). Mindset: The new psychology of success. Random House.

Evans, D. Stop Pondering, Start Prototyping. You Tube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yp3Vm3Epl2w

Institute of Coaching. Designing Your Life: Coaching to Get Unstuck and Thrive. YouTube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DHD653QQ8sc

Johnson, R. (2023, May 5). New survey finds most college grads would change majors. Best Colleges. https://www.bestcolleges.com/news/college-grads-change-majors/

Kitch, B. (2023). Prototyping: a guide to the 4th stage of design thinking Mural.com

National Center for Education Statistics (NCES). (2017). Percentage of 2011–12 First Time Postsecondary Students Who Had Ever Declared a Major in an Associate’s or Bachelor’s Degree Program Within 3 Years of Enrollment, by Type of Degree Program and Control of First Institution: 2014. Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education. Washington, DC. https://nces.ed.gov/datalab/tableslibrary/viewtable.aspx?tableid=11764.

Silver B. R. (2023). Major transitions: how college students interpret the process of changing fields of study. Higher education, 1–16. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-023-01050-8

Stanford Life Design Lab Worksheet. Odyssey Plan

US Department of Education (2017). Beginning College Students Who Change Their Majors Within 3 Years of Enrollment. https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2018/2018434.pdf

Yang, M.H. (2015) Emotions, Learning, and the Brain: Exploring the Educational Implications of Affective Neuroscience Norton

Additional Resources

Five Steps to Designing the Life You Want: Bill Burnett

Stop Pondering, Start Prototyping

Designing Your Life: Coaching to Get Unstuck and Thrive

Media Attributions

- Signs © Enguerrand Blanchy

- Most important identities © Lynn Meade

- Dysfunctional Beliefs © Lynn Meade