13 Basic Structure and Content of Argument

Amanda Lloyd; Emilie Zickel; Robin Jeffrey; and Terri Pantuso

When you are tasked with crafting an argumentative essay, it is likely that you will be expected to craft your argument based upon a given number of sources–all of which should support your topic in some way. Your instructor might provide these sources for you, ask you to locate these sources, or provide you with some sources and ask you to find others. Whether or not you are asked to do additional research, an argumentative essay should contain the following basic components.

Claim: What Do You Want the Reader to Believe?

In an argument paper, the thesis is often called a claim. This claim is a statement in which you take a stand on a debatable issue. A strong, debatable claim has at least one valid counterargument, an opposite or alternative point of view that is as sensible as the position that you take in your claim. In your thesis statement, you should clearly and specifically state the position you will convince your audience to adopt. One way to accomplish this is via either a closed or open thesis statement.

A closed thesis statement includes sub-claims or reasons why you choose to support your claim.

Example of Closed Thesis Statement

The city of Houston has displayed a commitment to attracting new residents by making improvements to its walkability, city centers, and green spaces.

In this instance, walkability, city centers, and green spaces are the sub-claims, or reasons, why you would make the claim that Houston is attracting new residents.

An open thesis statement does not include sub-claims and might be more appropriate when your argument is less easy to prove with two or three easily-defined sub-claims.

Example of Open Thesis Statement

The city of Houston is a vibrant metropolis with a commitment to attracting new residents.

The choice between an open or a closed thesis statement often depends upon the complexity of your argument. Another possible construction would be to start with a research question and see where your sources take you.

A research question approach might ask a large question that will be narrowed down with further investigation.

Example of Research Question Approach

What has the city of Houston done to attract new residents and/or make the city more accessible?

As you research the question, you may find that your original premise is invalid or incomplete. The advantage to starting with a research question is that it allows for your writing to develop more organically according to the latest research. When in doubt about how to structure your thesis statement, seek the advice of your instructor or a writing center consultant.

A Note on Context: What Background Information About the Topic Does Your Audience Need?

Before you get into defending your claim, you will need to place your topic (and argument) into context by including relevant background material. Remember, your audience is relying on you for vital information such as definitions, historical placement, and controversial positions. This background material might appear in either your introductory paragraph(s) or your body paragraphs. How and where to incorporate background material depends a lot upon your topic, assignment, evidence, and audience. In most cases, kairos, or an opportune moment, factors heavily in the ways in which your argument may be received.

Evidence or Grounds: What Makes Your Reasoning Valid?

To validate the thinking that you put forward in your claim and sub-claims, you need to demonstrate that your reasoning is based on more than just your personal opinion. Evidence, sometimes referred to as grounds, can take the form of research studies or scholarship, expert opinions, personal examples, observations made by yourself or others, or specific instances that make your reasoning seem sound and believable. Evidence only works if it directly supports your reasoning — and sometimes you must explain how the evidence supports your reasoning (do not assume that a reader can see the connection between evidence and reason that you see).

Warrants: Why Should a Reader Accept Your Claim?

A warrant is the rationale the writer provides to show that the evidence properly supports the claim with each element working towards a similar goal. Think of warrants as the glue that holds an argument together and ensures that all pieces work together coherently.

An important way to ensure you are properly supplying warrants within your argument is to use topic sentences for each paragraph and linking sentences within that connect the particular claim directly back to the thesis. Ensuring that there are linking sentences in each paragraph will help to create consistency within your essay. Remember, the thesis statement is the driving force of organization in your essay, so each paragraph needs to have a specific purpose (topic sentence) in proving or explaining your thesis. Linking sentences completes this task within the body of each paragraph and creates cohesion. These linking sentences will often appear after your textual evidence in a paragraph.

This section contains material from:

Amanda Lloyd and Emilie Zickel. “Basic Structure of Arguments.” In A Guide to Rhetoric, Genre, and Success in First-Year Writing, by Melanie Gagich and Emilie Zickel. Cleveland: MSL Academic Endeavors. Accessed July 2019. https://pressbooks.ulib.csuohio.edu/csu-fyw-rhetoric/chapter/basic-argument-components/. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Archival link: https://web.archive.org/web/20201027011022/https://pressbooks.ulib.csuohio.edu/csu-fyw-rhetoric/chapter/basic-argument-components/

Jeffrey, Robin. “Counterargument and Response.” In A Guide to Rhetoric, Genre, and Success in First-Year Writing, by Melanie Gagich and Emilie Zickel. Cleveland: MSL Academic Endeavors. Accessed July 2019. https://pressbooks.ulib.csuohio.edu/csu-fyw-rhetoric/chapter/questions-for-thinking-about-counterarguments/. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Archival link: https://web.archive.org/web/20201027003319/https://pressbooks.ulib.csuohio.edu/csu-fyw-rhetoric/chapter/questions-for-thinking-about-counterarguments/

OER credited the texts above includes:

Jeffrey, Robin. About Writing: A Guide. Portland, OR: Open Oregon Educational Resources. Accessed December 18, 2020. https://openoregon.pressbooks.pub/aboutwriting/. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Archival link: https://web.archive.org/web/20230711210756/https://openoregon.pressbooks.pub/aboutwriting/

Written Texts

When you analyze an essay or article, consider these questions:

- What is the thesis or central idea of the text?

- Who is the intended audience?

- What questions does the author address?

- How does the author structure the text?

- What are the key parts of the text?

- How do the key parts of the text interrelate?

- How do the key parts of the text relate to the thesis?

- What does the author do to generate interest in the argument?

- How does the author convince the readers of their argument’s merit?

- What evidence is provided in support of the thesis?

- Is the evidence in the text convincing?

- Has the author anticipated opposing views and countered them?

- Is the author’s reasoning sound?

Visual Texts

When you analyze a piece of visual work, consider these questions:

- What confuses, surprises, or interests you about the image?

- In what medium is the visual?

- Where is the visual from?

- Who created the visual?

- For what purpose was the visual created?

- Identify any clues that suggest the visual’s intended audience.

- How does this image appeal to that audience?

- In the case of advertisements, what product is the visual selling?

- In the case of advertisements, is the visual selling an additional message or idea?

- If words are included in the visual, how do they contribute to the meaning?

- Identify design elements – colors, shapes, perspective, and background – and speculate how they help to convey the visual’s meaning or purpose.

Examples

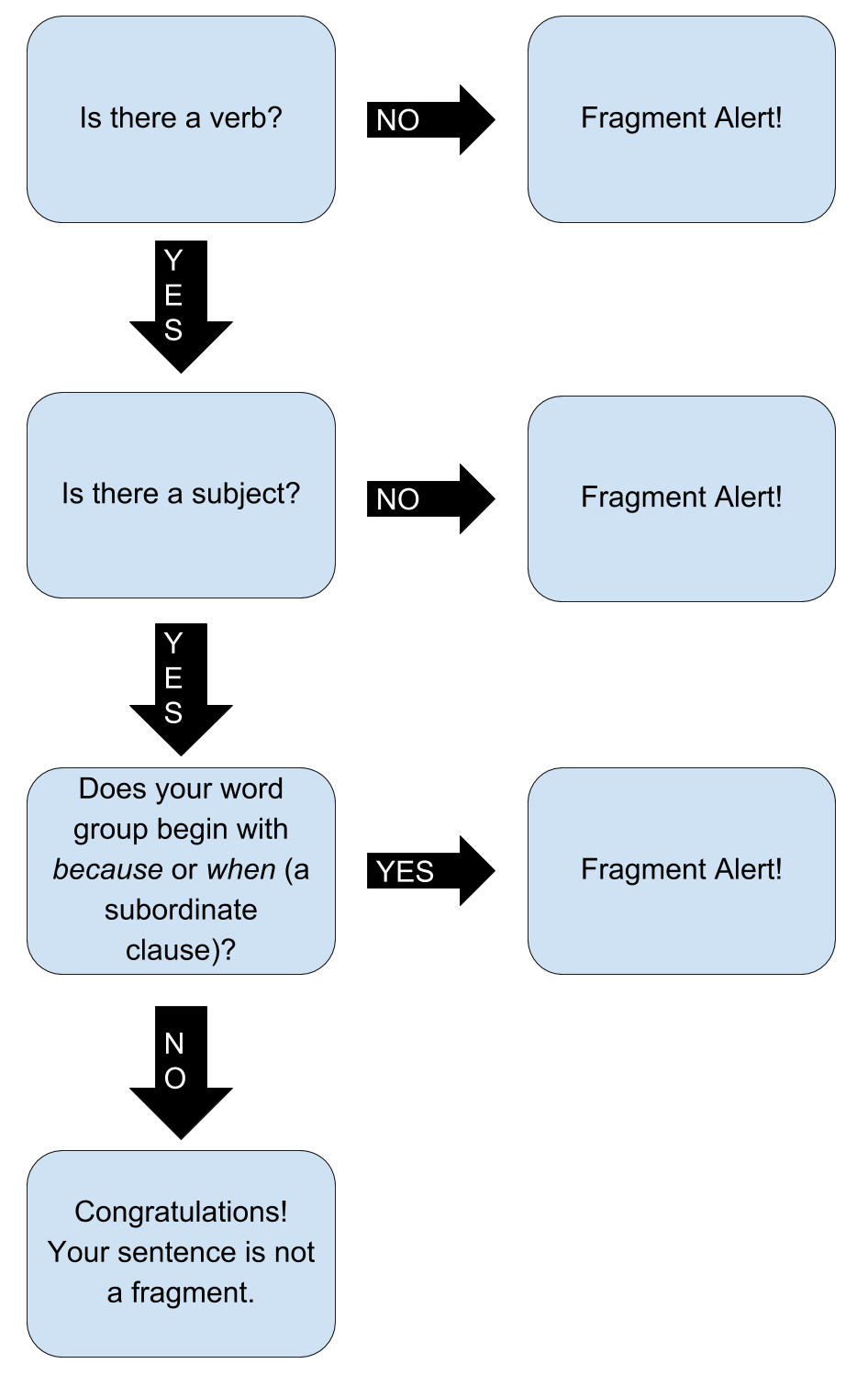

No Verb: A movie with pointless twists. VS. The movie has pointless twists.

No subject: For not doing her own homework, Missy was expelled. VS. Missy was expelled for not doing her own homework.

Beginning with Subordinate Clause: Because the band didn’t know the street address, the party was impossible to find. VS. The band couldn’t find the party because no one knew the address.